TL;DR

LightOn has released LateOn-Code, a family of state-of-the-art (SOTA) code retrieval models, along with ColGrep, a high-performance search tool designed to bring semantic intelligence directly to the developer's terminal.

The release aims to bridge the gap between traditional lexical search (like grep or BM25) and neural search for agentic tool, which has historically been too computationally heavy for local development environments.

The "Stronger Grep" for Modern Development

While AI coding assistants like Claude Code have transformed how code is written, their ability to navigate large codebases efficiently is often limited by keyword-based search. This frequently leads to "token burn", where agents waste thousands of tokens blindly searching files and hallucinations when the relevant context isn't found.

LateOn-Code and ColGrep solve this by providing:

- SOTA Performance with a Tiny Footprint: Two new models (17M and 130M parameters) that top the MTEB Code leaderboard. These ultra-compact models outperform significantly larger competitors while running instantly on a standard laptop.

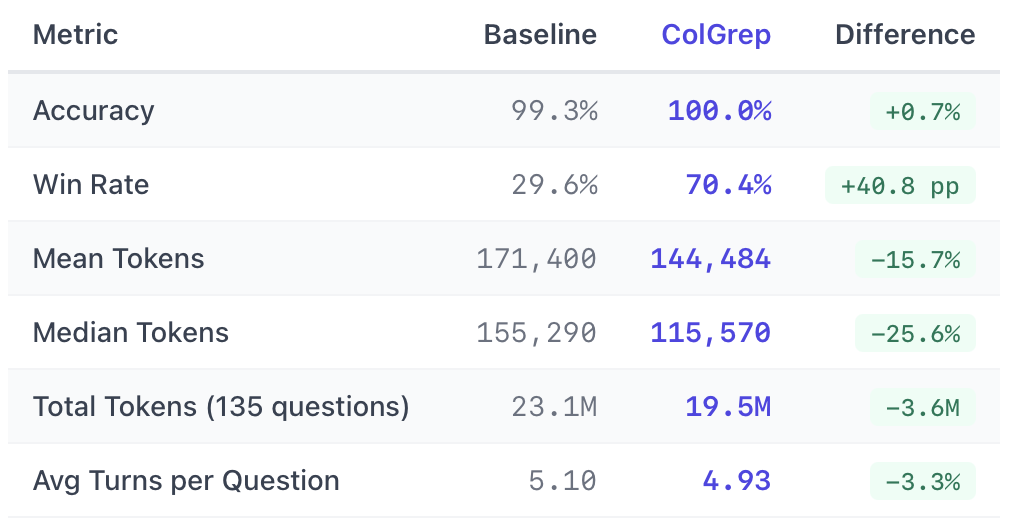

- 70% "Win Rate" for AI Agents: In benchmarks using Claude Code, ColGrep found the correct implementation details faster and with 56% fewer search operations than standard grep.

- Significant Cost Savings: Integrating ColGrep reduced token usage by an average of 60,000 tokens per complex query by providing surgical precision to the AI assistant.

- Hybrid Search Power: ColGrep introduces a "Stronger Grep" by bringing Late Interaction (ColBERT) directly to your local files. It creates a seamless synergy between precise file filtering and semantic intelligence, allowing you to surface code that matches both your specific syntax requirements and your high-level intent.

Powered by NextPlaid: ColGrep leverages an embedded Rust-based multi-vector database that enables neural-speed search locally. By eliminating cloud dependencies, this architecture ensures absolute privacy, all indexing and inference happen entirely on your machine, so your code never leaves your environment.

Technical Deep Dive

Late-interaction models have shown extremely strong out-of-domain, long-context, and reason-intensive retrieval capabilities. As detailed by Antoine in this talk, they share a lot with lexical methods such as BM25: the per-token representation avoids the aggressive compression of single-vector models, giving them similar strengths on out-of-domain and long-context retrieval. But they also circumvent the weaknesses of lexical search by leveraging deep learning to perform soft matching, making them robust when the query and the relevant document don't share the exact same terms. Code retrieval is a domain where these properties are especially relevant — and where lexical search is still dominant. Numerous coding agents still rely on basic grep to navigate codebases, and for good reasons: semantic search typically requires remote storage of sensitive code, and keeping an index in sync with a fast-moving codebase is hard. Yet the retrieval challenges agents face — finding relevant implementations across unfamiliar repositories, matching intent rather than exact keywords — are precisely the ones where late-interaction models excel. To the best of our knowledge, ColBERT-style models have not been publicly studied for code retrieval. To fill this gap, we introduce LateOn-Code, two late-interaction models specialized in code retrieval. Since we believe code retrieval should be performed locally, both models are small enough to run efficiently on CPUs while topping benchmarks well above their weight class. We then present ColGrep, a Rust command-line tool that makes these models practical: it reproduces the grep interface agents already know, augments it with semantic ranking and hybrid regex + semantic queries, and runs entirely locally with fast incremental index updates. When plugged to coding agent, it helps providing better answers while making it faster and consuming less tokens. We believe this is what code search for agents should look like.

LateOn-Code models

We pre-trained LateOn-Code models following the CoRNStack methodology, followed by a task-specific fine-tuning stage. Rather than training from scratch, we start from models already strong at general-domain search, since code retrieval frequently involves natural language: users and agents write queries in plain English, and documentation is ordinary text.

Base models

We started from the two best ColBERT models on the BEIR benchmark for their respective sizes. The first is our in-house LateOn model, a new version of GTE-ModernColBERT-v1 built on ModernBERT-base (also developed at LightOn). This version underwent significantly deeper training, crossing the 57 mark on BEIR, almost a 2.5-point improvement and is thus SOTA by a large margin. We'll release this base model along with training data and boilerplates in the near future, so stay tuned!

LateOn-Code-edge is a smaller model based on the edge-colbert model family from mixedbread, using the smallest variant (Ettin-17M) for maximum efficiency.

Besides being very strong ColBERT models on their own, we chose these models because they are both ModernBERT-based, and besides the satisfaction of further enhancing our own models, we know these models have been carefully crafted with code support right from the start.

Training

Pre-training

We use the CoRNStack data to pre-train our models, which covers 6 languages (Go, Java, JavaScript, PHP, Python, and Ruby). Each sample pairs a text docstring with its corresponding function as the positive document, along with mined hard negatives. We refer readers to the CoRNStack paper for details on the data creation process.

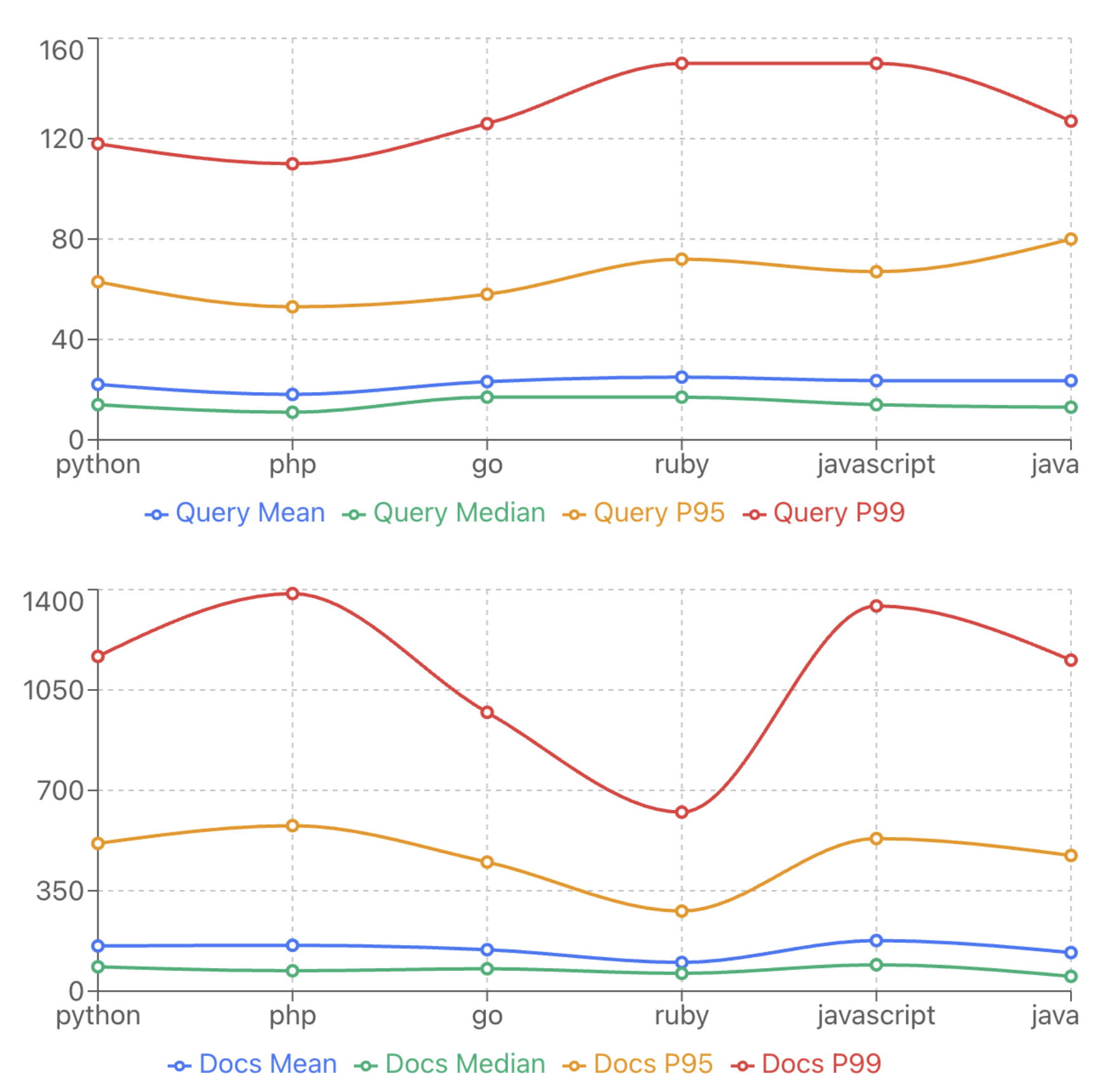

Since the carefully mined negatives remove the need for large batch sizes, we train with a standard supervised fine-tuning setup using a batch size of 128. Code retrieval involves notably longer queries and documents than typical retrieval setups. Multi-vector models are known to generalize well to longer documents than seen during training, this is less established for queries (though we observed some generalization). Thus, training on long inputs when possible remains preferable. We found that query and document lengths of 256 and 2048 respectively cover the vast majority of the training data. These values fall short of the evaluation datasets, but we do not have longer training data available.

We train with standard contrastive learning, ensuring each batch contains samples from a single language split to prevent shortcut learning across languages. The main difference from the usual PyLate contrastive setup is softmax-based negative sampling from CoRNStack: instead of keeping only the top-k negatives or sampling randomly, we use the mining scores to derive sampling probabilities via softmax. This keeps the focus on the hardest negatives while preserving some diversity. We sample 15 negatives per query at each step with a temperature of 0.05 (heavily peaked on the hardest negatives). The CoRNStack authors report that a curriculum on the temperature, starting high for diversity and decreasing through training, is beneficial. Our quick tests showed no significant difference, so we kept the temperature fixed, though more thorough experimentation might yield gains on some datasets.

Fine-tuning

While our pre-trained models already achieve very competitive results on MTEB Code (notably on CodeSearchNetwork), some competitors scored much higher on the AppsRetrieval dataset while being worse or equal on other splits, a gap hidden by the average score. As this was most likely a domain issue, we fine-tuned on the training sets of the various CoIR datasets. Following the nv-retriever methodology, we filter out mined negatives with similarity above 99% of the positive score. We keep 50 negatives per query, randomly sample 15 per step, and train with a batch size of 128. To enable reproduction and extension, we release the unfiltered data with 2048 mined negatives per sample alongside their scores, so anyone can choose their own filtering threshold. This fine-tuning drastically improves performance, both by adding new capabilities (training on tasks beyond documentation-to-code) and by bringing the model in domain.

Results

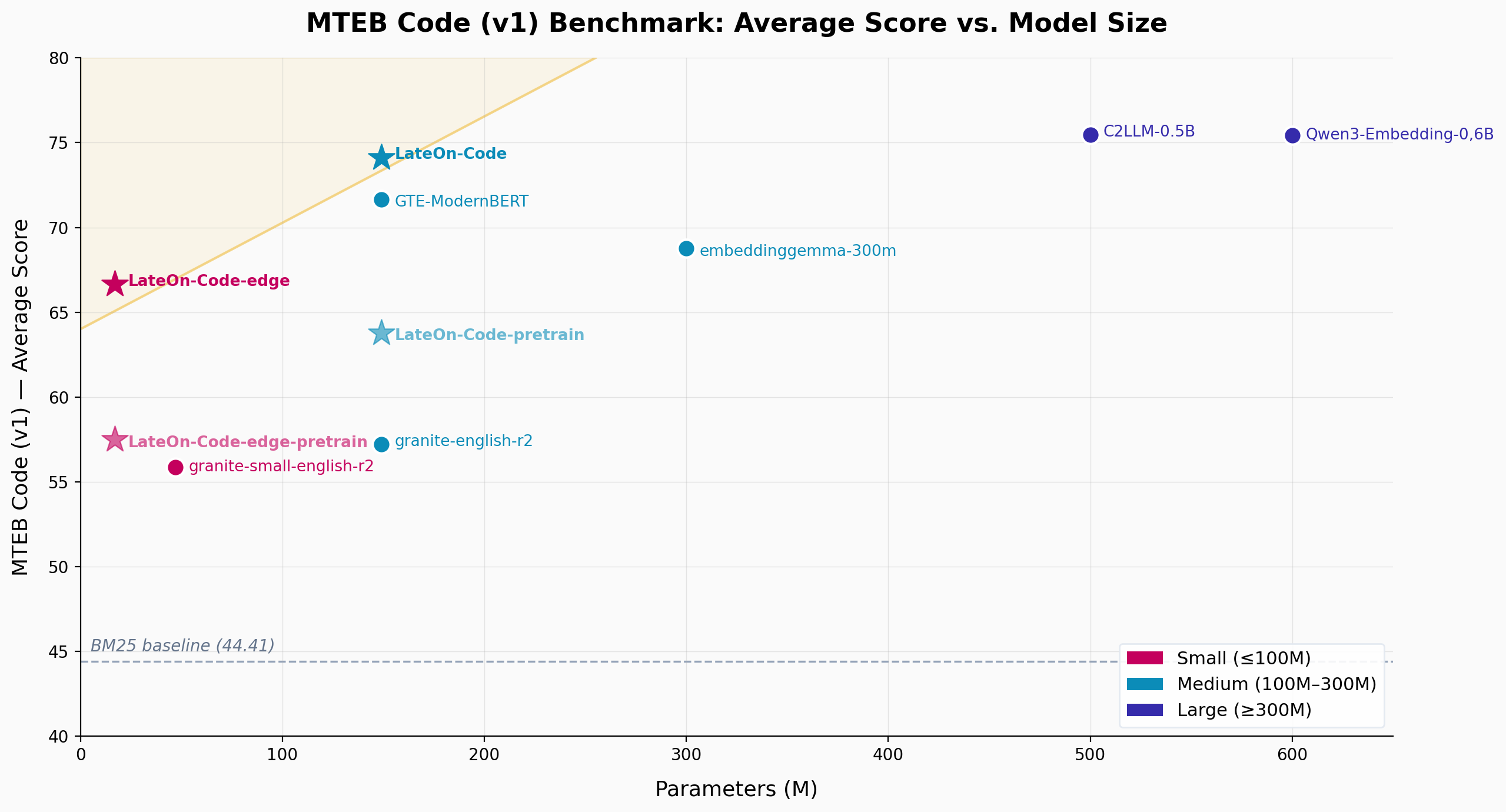

We report results on the MTEB(Code, v1) benchmark for both LateOn-Code models alongside main competitors. Due to memory constraints, we evaluate LateOn models with max query and document lengths of 1024 and 2048 respectively. We also include BM25 scores as a reference point for lexical search (similar to grep). Dataset descriptions are provided below.

Pre-Training models

Let's first look at the pre-training results, before any task-specific fine-tuning.

The pre-trained LateOn-Code-edge beats granite-embedding-small-english-r2 by 1.7 on average, despite being almost three times smaller (17M vs 48M). Even more impressively, it also outperforms the larger granite variant (149M). The first model on the leaderboard to actually surpass it is EmbeddingGemma-300M, a very strong model 17 times its size.

The pre-trained LateOn-Code scales nicely, improving over its smaller sibling by 6.5 on average. Since the edge variant already tops the <300M category, there are few new models to compare against, though the pre-trained LateOn-Code still falls behind Gemma-300M overall. However, the average hides a more nuanced story: on several datasets, both pre-trained models match or beat EmbeddingGemma-300M, including, surprisingly, the edge variant.

The weak spot is AppsRetrieval, where the pre-trained models score poorly (10.5 and 23 vs. 84.4), which drags down the average significantly. Without this dataset, the pre-trained models are even more competitive than they appear. This is surprising since AppsRetrieval is a natural language to code retrieval task, exactly the type our models excel at (see CodeSearchNetRetrieval). This may be partly due to evaluation length limitations imposed by benchmark size, but CodeRankEmbed, also trained on CoRNStack, achieves similarly poor results. This points to a domain gap, motivating the fine-tuning stage described next.

Fine-tuned models

The pre-training results are already impressive given they are mostly out-of-domain, but fine-tuning on CoIR training data significantly boosts performance. The 17M model jumps from 57.50 to 66.64 (+9.14), approaching EmbeddingGemma-300M while being 17 times smaller. The 130M model jumps from 63.77 to 74.12 (+10.35), strongly outperforming EmbeddingGemma-300M and closing in on much larger LLM-based models such as Qwen3-Embedding-0.6B and C2LLM-0.5B.

While fine-tuning improves the vast majority of datasets, some see slight degradation. Our goal is not just to claim SOTA on a leaderboard but to create genuinely useful models, so we sought the best compromise by merging models. Some of our individual fine-tuning runs achieved higher averages, but we prioritized preserving the original capabilities rather than maximizing the overall score. Although ColBERT models are known to be strong out-of-domain, a large part of the fine-tuning gains come from becoming in-domain, which could mask regressions on real-world use cases. We release both the pre-trained and fine-tuned models so users can perform their own fine-tuning or experiment with the original models directly.

Best result across all sizes is underlined. Best within each size category is bolded.

Conviced by the results and want to try out the models/use the data? Have a look at the HuggingFace collection.

ColGrep

Autonomous coding agents such as Claude Code search codebases using grep. They avoid semantic search for good reasons: it typically requires remote storage of sensitive code, and keeping an index in sync with a fast-moving codebase is hard. Despite semantic search proving useful, especially for large codebases (Gu et al., 2018; Husain et al., 2019), agents still manage to find what they need through trial and error, so why bother?

ColGrep is our answer. It is a Rust command-line program that reproduces the grep interface agents already know, but augments it with the semantic and intent-detection capabilities of late-interaction models. Powered by LateOn-Code and Next-Plaid, our multi-vector database written in Rust, ColGrep runs entirely locally: no remote storage, no separate API service, and fast incremental index updates triggered by any file change. It is specifically designed for coding agents such as Claude Code, OpenCode, or Codex, which search for relevant implementation details before proposing edits or generating patches. Crucially, ColGrep also supports hybrid queries: agents can apply regex constraints first, exactly as they would with grep, and then let the semantic model rank the filtered results by intent, getting the best of both worlds.

Get started in 30 seconds:

# Install

curl --proto '=https' --tlsv1.2 -LsSf https://github.com/lightonai/next-plaid/releases/latest/download/colgrep-installer.sh | sh

# Index your project

colgrep init ./path/to/your/project

# Search

colgrep "database connection pooling"

# Plug into Claude Code

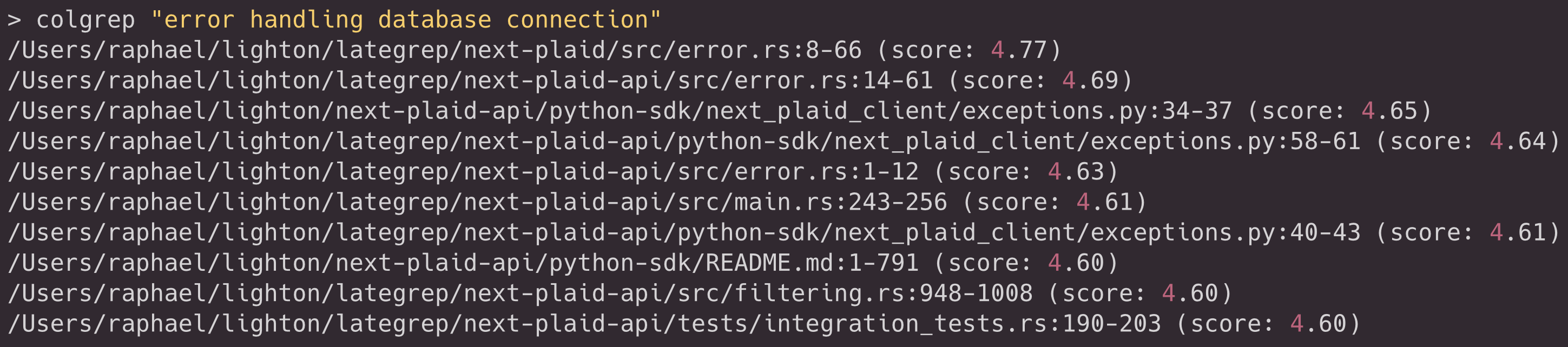

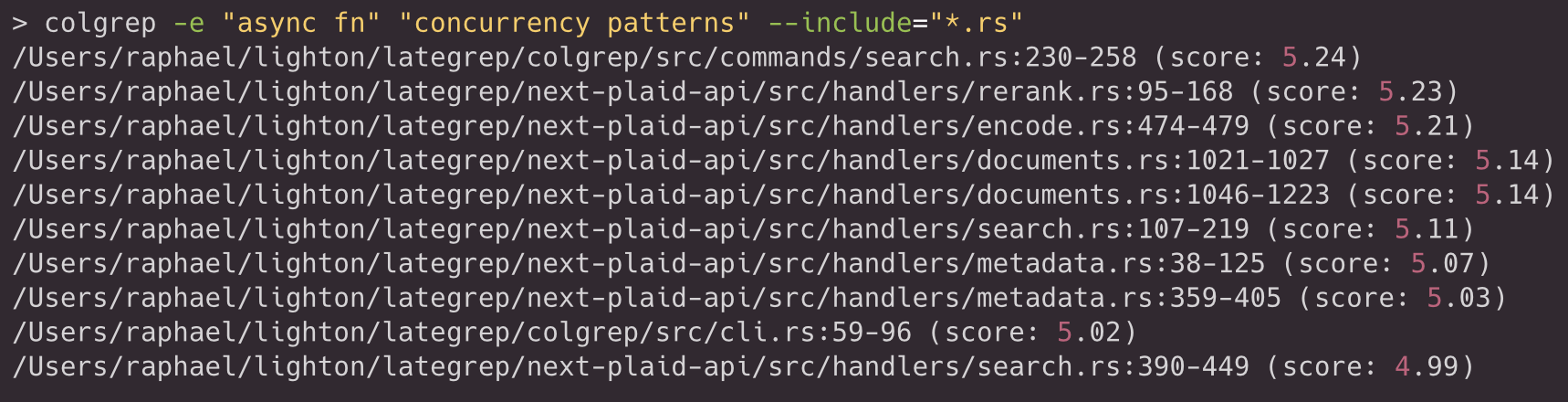

colgrep --install-claude-codeA typical session begins with a query phrased in natural language:

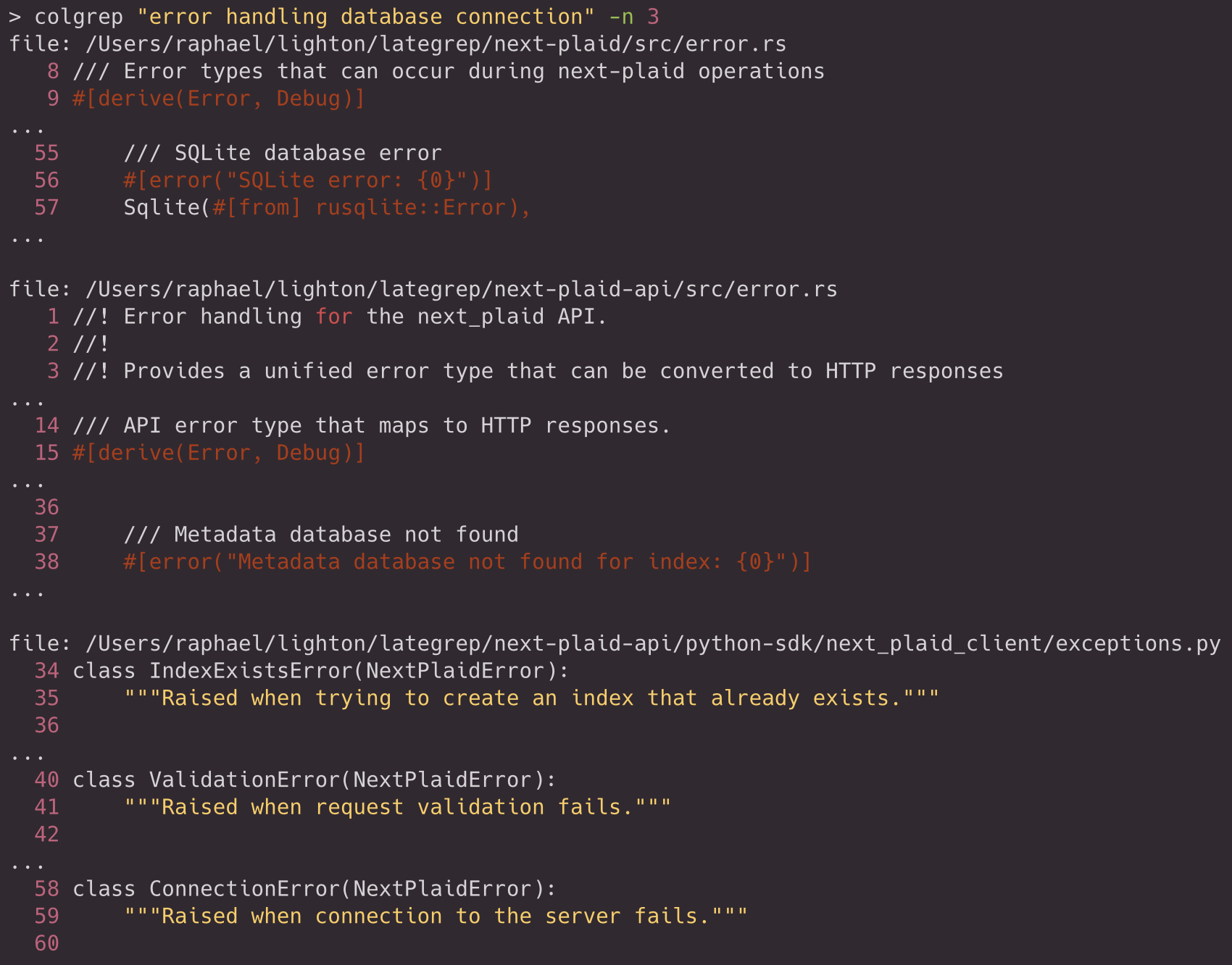

The coding agent can switch to a verbose mode on demand and choose the number of lines to display:

Parsing

The first time you query ColGrep, it scans the current directory, encodes every code block it finds, and stores the resulting embeddings in an on-disk multi-vector database. Because the database is embedded in the client, neither a human user nor a coding agent needs to start or manage a separate API service. Communication between the client, the model, and the vector database happens directly in Rust rather than over HTTP.

Colgrep parses the current folder while respecting ignored rules (from .gitignore) and excluding directories that mostly contain generated or third party content. It also enforces a file-size ceiling, which reduces the probability that minified bundles or machine output dominate the token distribution. The effect is that indexing focuses on the parts of the repository that usually carry meaning.

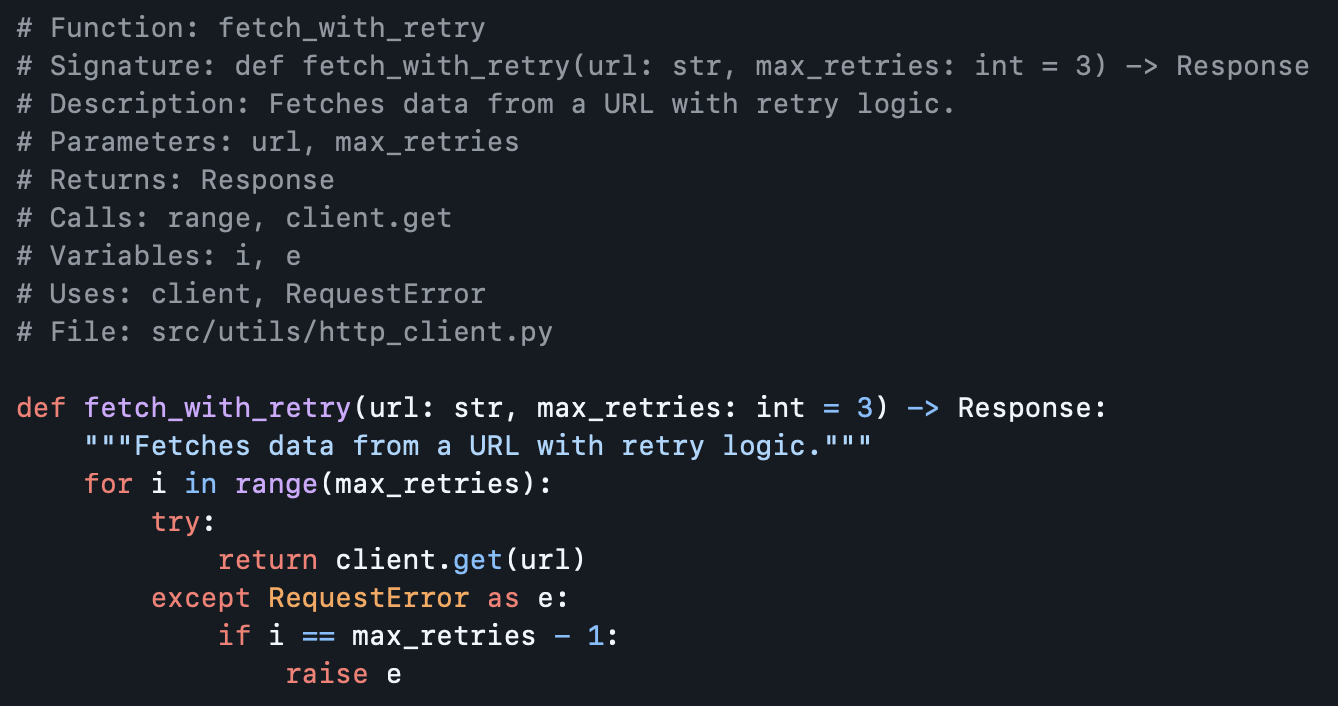

Colgrep parsing converts files into code units. For supported programming languages, tree-sitter produces an AST that is used to extract units such as functions, methods, and type blocks. For documentation and configuration files, ColGrep falls back to document-style units so these artifacts remain searchable. Where structural extraction leaves gaps, the system emits additional RawCode units so that top-level statements, import sections, and loose initialization logic are still indexed. This coverage property matters for retrieval, because many “where is X configured?” queries resolve to fragments that are not inside a function.

The representation sent to the model is not raw code alone. ColGrep performs layered static analysis and serializes the result into a structured text form. The AST layer supplies interface evidence such as names, signatures, parameter lists, return annotations, and doc comments. A call graph layer adds relational context: calls are collected within each unit during AST traversal and then resolved globally to populate both “calls” and “called by” fields. Additional layers add coarse summaries of control flow, variable bindings, and dependencies, with dependencies filtered to emphasize those that appear referenced in the unit. The output is a compact record intended to make the unit searchable by intent without requiring the query to match exact syntax.

ColGrep supports Python, TypeScript, JavaScript, Go, Rust, Java, C, C++, Ruby, C#, Kotlin, Swift, Scala, PHP, Lua, Elixir, Haskell, OCaml, R, Zig, Julia, SQL, Vue, and Svelte with full tree-sitter parsing for structural extraction, plus HTML, Markdown, Plain Text, YAML, TOML, JSON, Dockerfile, Makefile, Shell/Bash, PowerShell, AsciiDoc, and Org as document-style formats.

A simplified example of the constructed text looks like:

Because the multi-vector database supports incremental updates, ColGrep avoids re-indexing unchanged files. On the first run, ColGrep computes a content hash for each indexed file and stores it alongside the embeddings. On subsequent runs, it compares the current hash of each file against the stored one. Files whose hash matches are skipped entirely: no parsing, no embedding call, no database write. Only new or modified files go through the full pipeline.

This keeps the cost of search aligned with the common development pattern of small edits and frequent queries. A developer who pulls a branch with a handful of changed files pays only for those changes, not for the entire repository. The same applies to coding agents that invoke ColGrep repeatedly during a session: the first query builds the index, and later queries benefit from near-instant startup. The next time an agent will spawn, it will reuse the existing index.

The hash-based approach also handles deletions gracefully. When a file disappears from the working tree, its entries are pruned from the database so stale results never surface in queries.

Inference

ColGrep uses LateOn-Code-edge as its default model, though it can be swapped out. It runs on ONNX Runtime and is int8-quantized by default.

To support multi-vector scoring at interactive latency, ColGrep uses Next-Plaid. It clusters token vectors into centroids and stores them in an inverted structure to retrieve candidates without scanning the entire corpus. It also quantizes residuals to shrink storage and keep approximate scoring inexpensive. The resulting index is saved as memory-mapped files, so queries can run without preloading everything into memory and the OS can page in only the portions that are actually accessed.

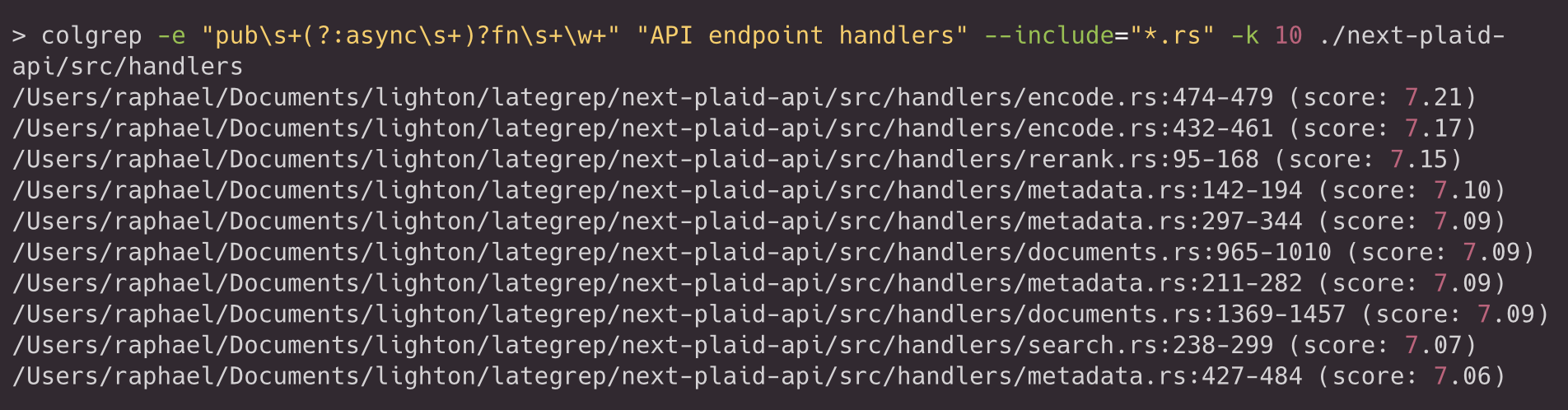

Metadata is persisted in SQLite, and ColGrep uses SQL filtering before vector scoring. This supports hybrid usage where a lexical constraint is applied first and semantic ranking is applied second. For example, an agent can require that candidate units contain a Rust async function signature, and then ask for semantic ranking within that subset:

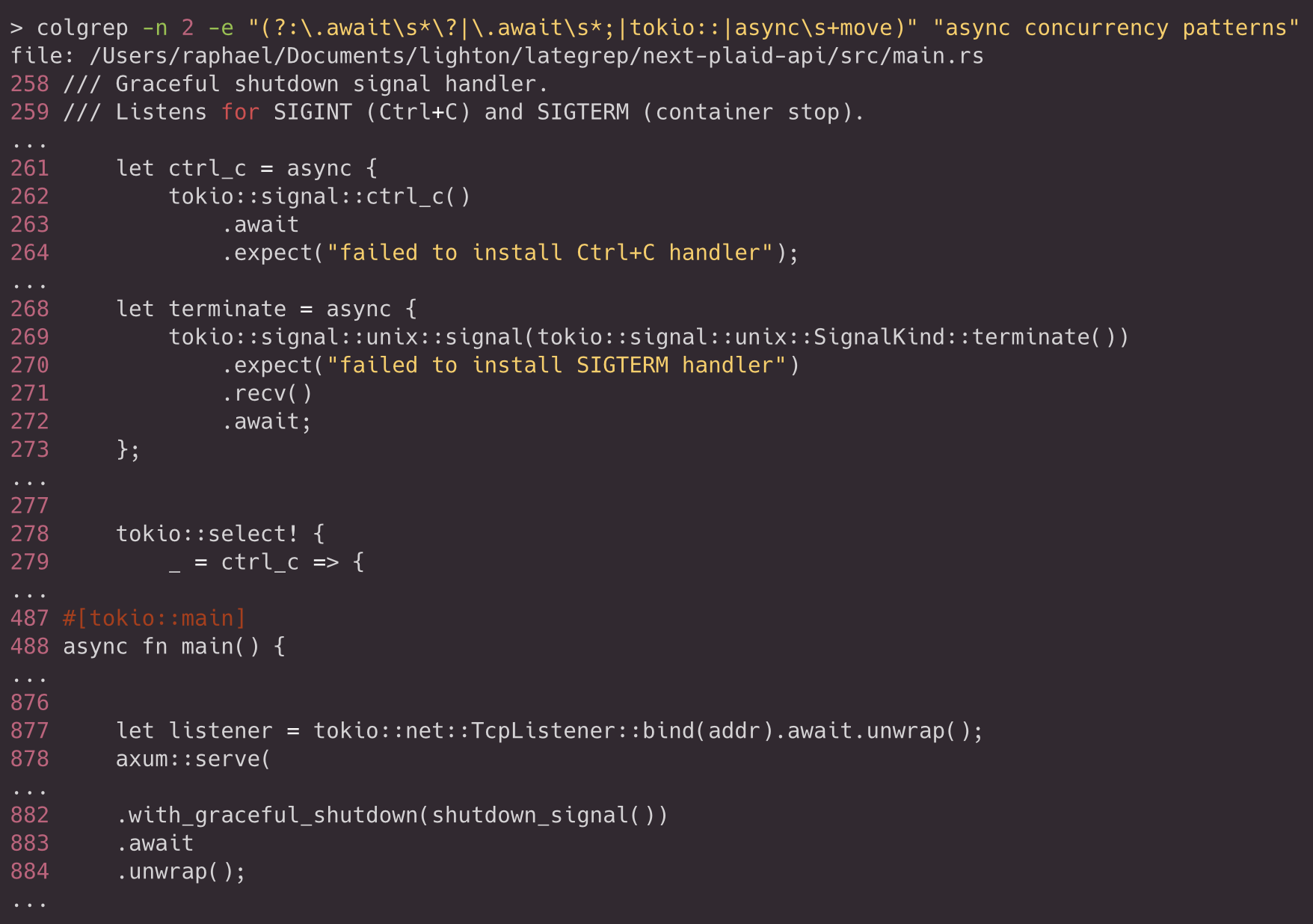

In practice, this filtering stage is also where more elaborate regular expressions become useful, because the filter is applied before semantic ranking. For example a regex which find code that awaits futures (with or without error propagation), uses the tokio runtime, or creates async closures that take ownership of their environment:

While regexes are not human friendly, coding agents largely benefit from this feature and are eager to use it. Grep brings to the agents a way to reduce the search space to highly relevant candidates. Within ColGrep, Grep is emulated using Sqlite filtering queries against our multi-vector database.

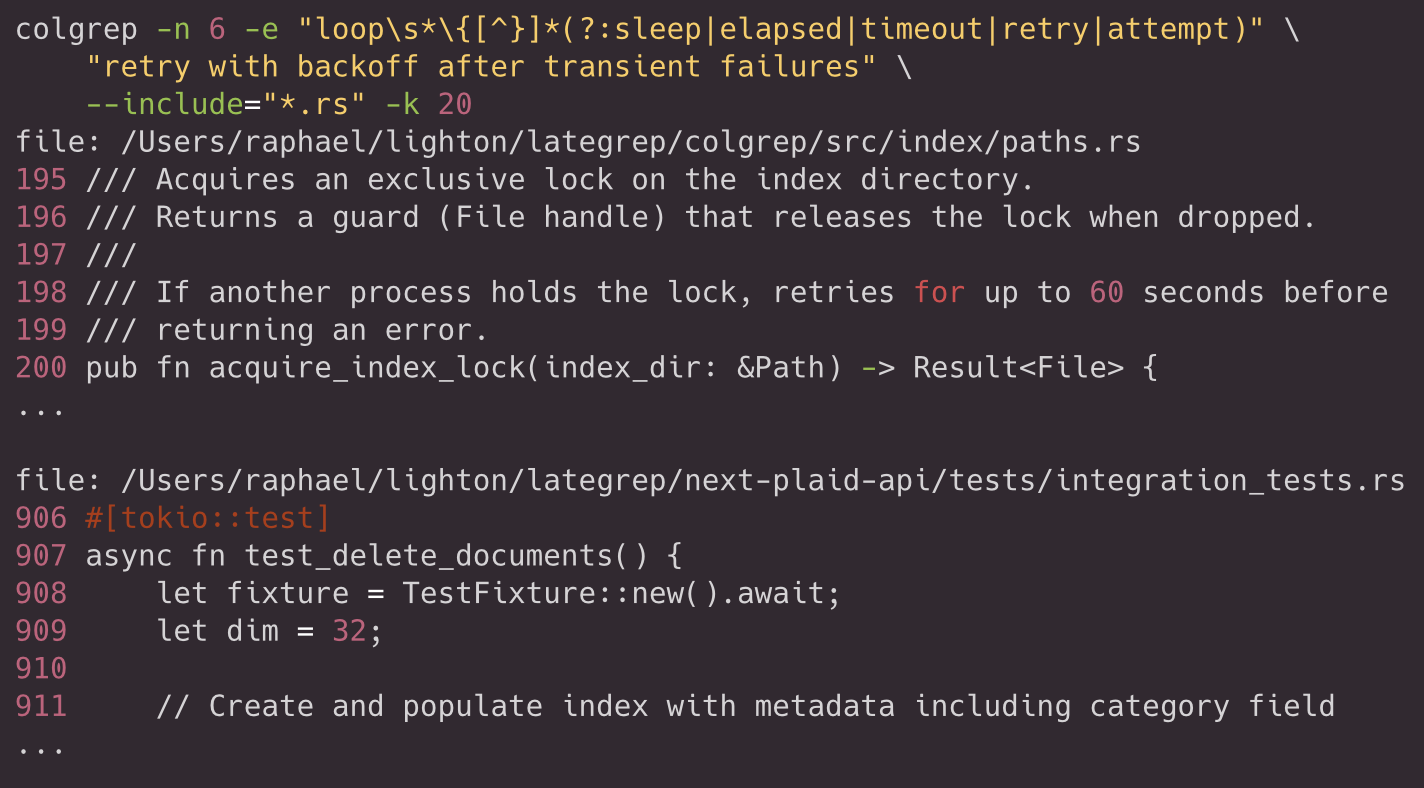

Another example is searching for idiomatic Rust retry patterns, while ranking by intent about backoff logic. The regex constrains the candidate set to infinite loops containing timing-related keywords (sleep, elapsed, timeout, retry, attempt), then the semantic query prefers those that implement exponential backoff or transient failure recovery:

Like grep, searches can be scoped by directory, file path, or extension pattern. Find the top 3 public functions in the API handlers directory that are most semantically relevant to endpoint handling, filtering only Rust:

For scripting and evaluation, JSON output exposes the file, unit metadata, and score:

When providing -n flag to the search to switch to verbose mode, ColGrep selects representative lines by scoring token overlap between query terms and code text. It then computes context windows around those lines, merges overlapping windows, and ensures that signatures remain visible even when the representative line lies deep in the body of a function for example.

End-to-end, the system is best understood as a pipeline: repository traversal defines the corpus, parsing partitions files into units, analysis transforms units into structured representations, embedding produces multi-vector features, and a PLAID-style index supports late-interaction scoring at low latency. The command line surface remains compact, but the internal sequence is explicitly engineered to make intent-level queries viable on real repositories.

Evaluation

We built ColGrep to give coding agents a search tool that understands intent and semantics and supports fuzzy matching, so they can find relevant code without knowing exact identifiers. In practice, many agents still rely on iterative grep because it often works as well as, or better than, vector search. So the key question is: does ColGrep outperform traditional grep? To answer it, we ran a systematic evaluation on several standard open-source codebases.

We designed the benchmark to answer three questions. First, does ColGrep help agents find the right code? Second, does ColGrep reduce resource consumption? Third, does ColGrep speed up navigation?

We used Claude Opus 4.5 within Claude Code with two distinct settings to perform the evaluation.

- Baseline: Claude Opus 4.5 with Claude Code vanilla.

- ColGrep: Claude Opus 4.5 with Claude Code with ColGrep installed and LateOn-Code-edge model.

Our evaluation will focus on question answering over popular repositories available on github.

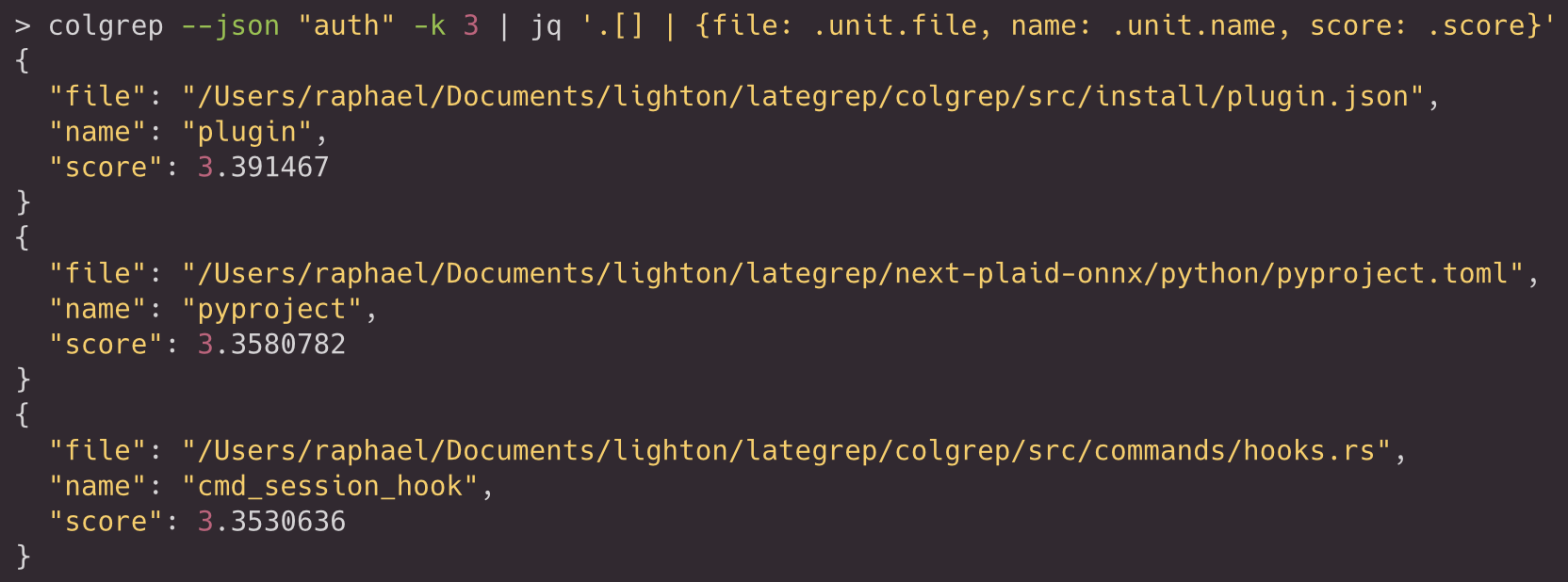

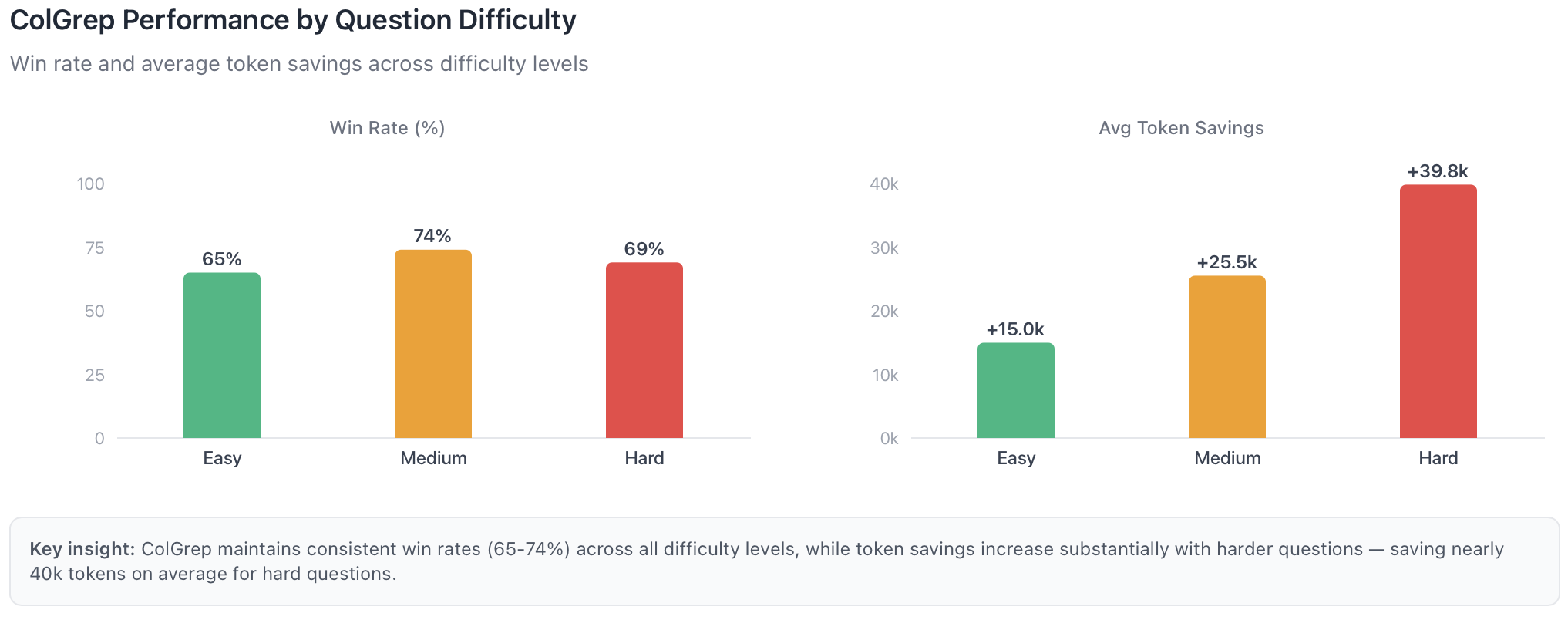

We asked Claude Code to generate 135 code retrieval questions spanning three difficulty levels. Easy questions ask for well-known entry points. Medium questions require understanding module boundaries. Hard questions describe functionality without naming the implementation. We create a dedicated Claude Code session for each question.

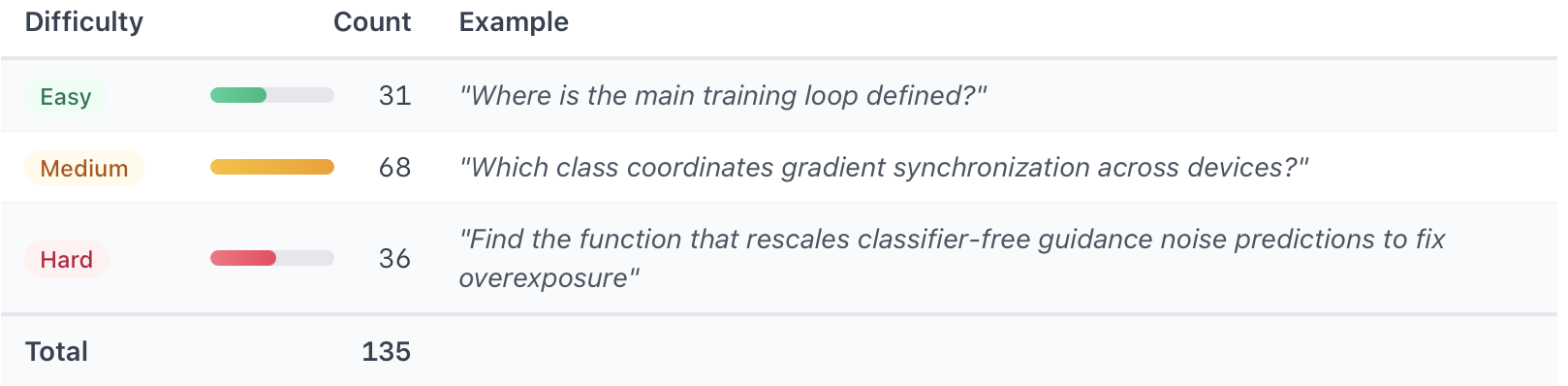

We computed the win rate on the question answering task by analyzing the coding agent traces with Opus 4.5 as a judge. It attributed the point to the coding agent with the best trace that yielded to an exact answer.

Both the baseline and ColGrep successfully answered most questions, but they differed markedly in the effort required to get there. In direct head-to-head comparisons, Opus 4.5 judged ColGrep’s answers better in 70% of cases. Moreover, when ColGrep was preferred, it achieved those wins with substantially less interaction, reducing usage by about 60,000 tokens per question on average.

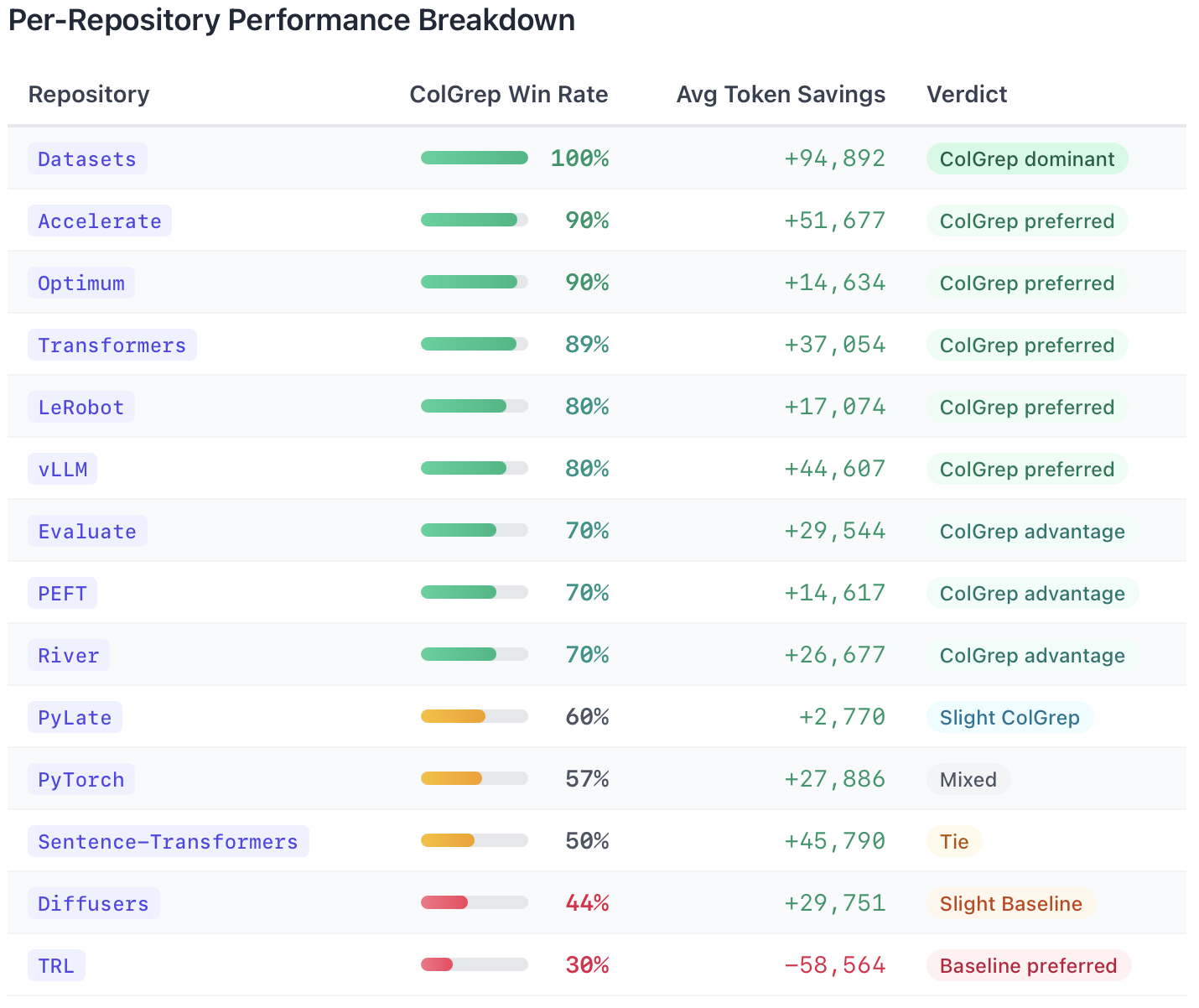

Performance varies by repository. ColGrep dominates Datasets repository, where it won every single question. It also performs well on Accelerate, Optimum, and Transformers repositories. We think these codebases reward semantic understanding because they use descriptive but non-obvious naming conventions.

Biggest Wins

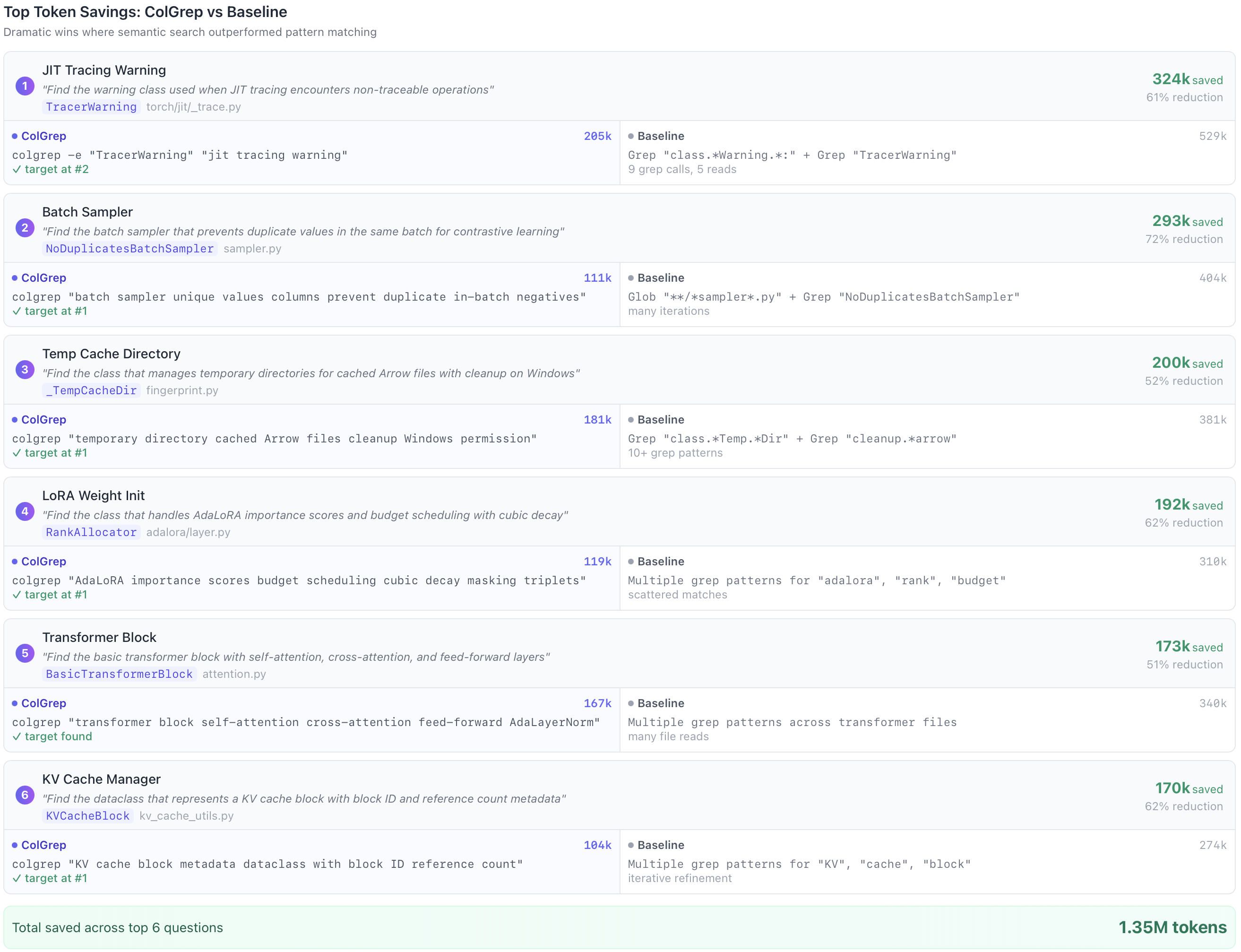

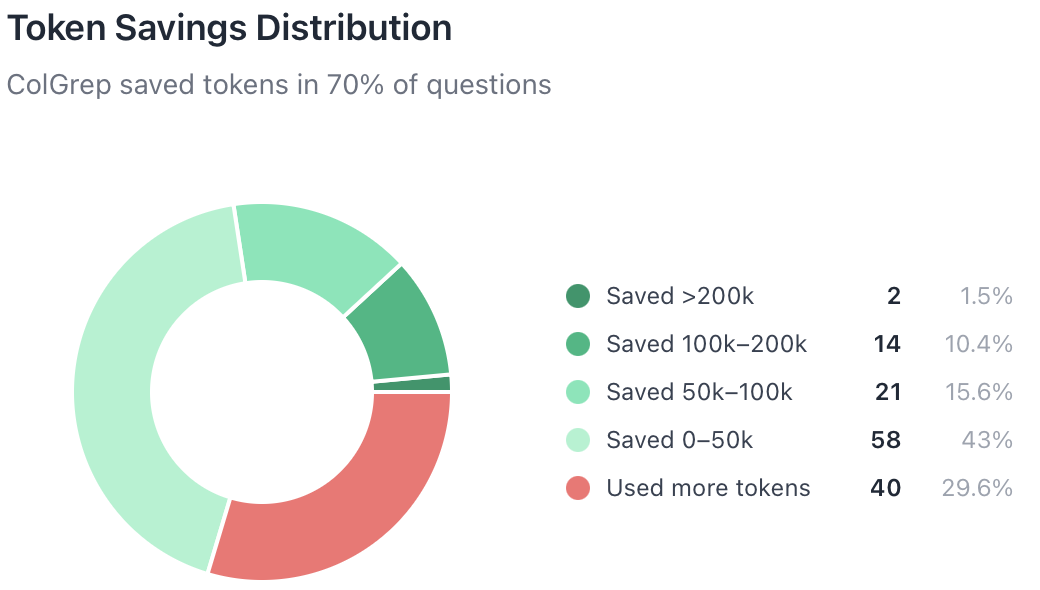

Some questions showed dramatic token savings. The top ten success cases saved between 159,000 and 324,000 tokens each: reductions of 50% to 72% compared to baseline.

Conceptual questions about caching, synchronization, and configuration benefit most from semantic search. These queries describe behavior rather than naming functions directly.

The TRL Exception

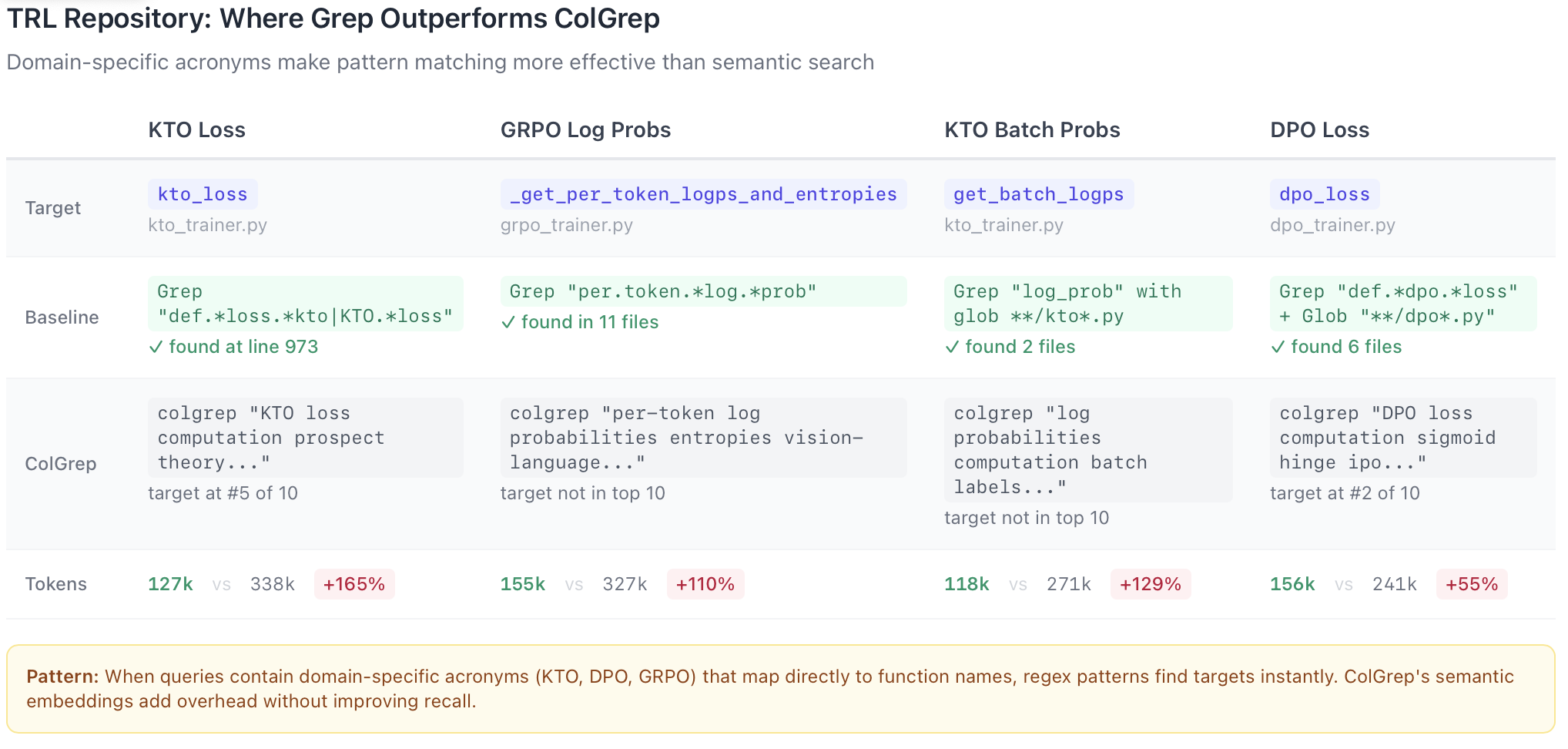

TRL is the one repository where baseline consistently outperforms ColGrep. TRL uses highly descriptive function names that grep matches directly. When the question contains the exact identifier, pattern matching finds it immediately. Semantic search returns broader results that require refinement.

Harder questions show larger gains. On easy questions, ColGrep wins 65% of the time with modest savings. On hard questions, the win rate is 69% but the average savings nearly triple. This pattern makes sense. Easy questions often have direct keyword matches. Hard questions describe functionality in natural language, which is exactly what semantic embeddings capture.

For teams running thousands of agent queries each day, a 15.7% reduction adds up rapidly. That said, our evaluation measures question answering over a large codebase, so the results may not carry over directly to coding tasks, or they may scale differently in that setting. We also ignored caching which can reduce cost to get comparable comparisons.

Not every question produces massive gains. ColGrep saved tokens in 70% of questions. The wins concentrate in the moderate savings bracket (0–50k), but the large wins (>50k) account for 27.5% of cases and drive most of the aggregate benefit.

ColGrep reduces the number of search operations required to answer a question. Baseline agents issue grep and glob commands repeatedly, refining patterns until they find what they need. ColGrep typically returns useful results on the first or second query. ColGrep requires 56% fewer search operations than baseline. This efficiency compounds: fewer searches mean fewer tool calls, fewer tokens spent on intermediate results, and faster convergence to the answer.

ColGrep saves the most tokens in two situations. First, on complex questions, especially those that are token-heavy under the baseline, where semantic search helps with navigation. Second, when it reduces the number of turns, it almost always reduces tokens too because the search is more direct.

Overall, ColGrep wins on both fewer turns and fewer tokens in 49% of questions. Even in the 13% where it takes more turns, it still saves tokens overall because each turn retrieves more useful results.

Hybrid Search

ColGrep avoids forcing a trade-off between semantic and lexical search by supporting hybrid queries. It first applies a regex constraint, as grep does, and then performs semantic ranking on the remaining results.

This is especially useful for coding agents. An agent can insist that candidates include a specific pattern, such as an async function signature or a particular decorator, and then request semantic ranking within that filtered set. The regex step shrinks the search space to highly relevant candidates, and the semantic model then orders them by intent.

For instance, if an agent is looking for retry logic with exponential backoff, it can start by filtering for code that contains timing-related keywords like sleep, timeout, retry, or attempt, and then rank those matches by similarity to “exponential backoff with transient failure recovery.” The regex filter removes many false positives, while semantic ranking brings the most relevant implementations to the top.

This hybrid design is also why ColGrep does not simply replace grep. It incorporates grep’s strengths while extending them. Agents that combine lexical filtering followed by semantic ranking can consistently outperform either method used on its own.

Limits

The ColGrep coding agent received auto-injected instructions via a hook on how to use ColGrep instead of grep. Yet even with clear guidance, agents didn’t fully exploit ColGrep’s capabilities, which points to an opportunity. An agent explicitly trained or more strongly prompted to use semantic exploration, hybrid filtering, and lean output mode would likely widen the gap. Our 70% win rate came from a general-purpose agent discovering ColGrep’s value organically, and a specialized agent could push it higher.

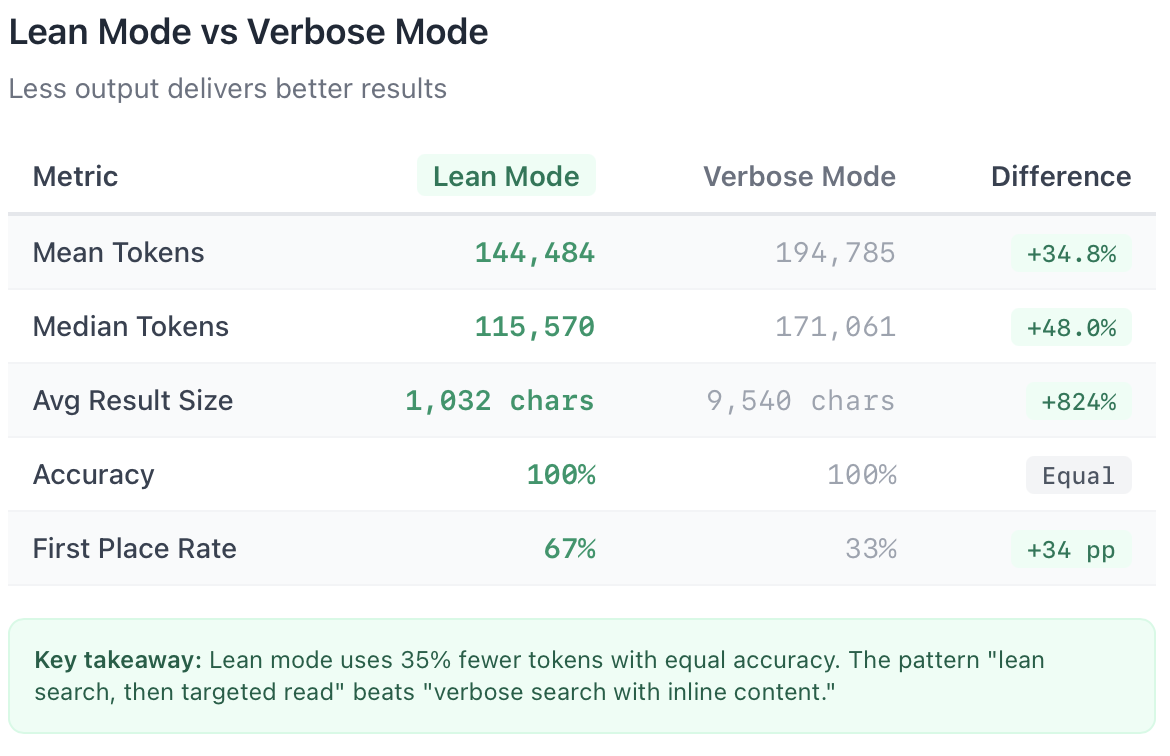

Verbose mode, case study

ColGrep offers a verbose -n option that adds line numbers and broader code context to its output. We evaluated both settings, and the results clearly favor the lean mode without -n.

In our experiment, verbose mode produced about nine times more text per query without improving accuracy. That added context inflates the conversation, prompts longer follow-ups, and ultimately consumes more tokens to reach the same answer. When ColGrep returns larger code blocks, the agent ends up sifting through redundant material and often revisits the same content anyway.

Key Takeaways

ColGrep provides clear gains for semantic code search. In head-to-head comparisons it wins 70% of the time, cuts token usage by 15.7% on average, and handles difficult conceptual questions better than pure pattern matching. Verbose mode adds cost without corresponding benefits, while lean output plus targeted file reads consistently beats inline code expansion. Minimal output should be the default.

ColGrep also enables hybrid queries that pair grep-style regex filtering with semantic ranking. This extends and effectively subsumes traditional pattern matching rather than replacing it. Agents that first narrow candidates with regex constraints and then apply semantic ranking can achieve results neither approach reaches on its own.

The best agent strategy combines these ideas: use ColGrep for semantic exploration, switch to hybrid filtering when you know partial patterns, and keep outputs lean unless you need line-level precision right away. An agent trained specifically on these behaviors would likely surpass the 70% win rate achieved with general-purpose prompting.

- Start saving tokens with ColGrep right now → Installation & CLI examples

- Find models, data and code → HuggingFace collection

- Train your own state-of-the-art model with PyLate → PyLate

We thank the reviewers of this BP for their valuable feedback, Amélie Chatelain, Iacopo Poli and Tom Aarsen

.svg)

.avif)

.avif)