TL;DR

LightOn is adding a new core capability to Paradigm: LightOn NextPlaid, a CPU-optimized multi-vector database exposed through a lightweight API. Designed to run alongside your existing vector database, it lets teams add multi-vector retrieval to their RAG stack with minimal integration, improving retrieval speed and precision while reducing the amount of context the LLM needs to consume.

NextPlaid is the Blanc step in LightOn’s Bleu / Blanc / Rouge roadmap for enterprise document intelligence. After Bleu (LightOnOCR-2, turning complex documents into clean text), Blanc delivers the on-prem, production-ready search layer—with Rouge next, pushing retrieval further with a new generation of enterprise search models.

There are major opportunities to improve corporate search across CRMs, emails, ERPs, document storage, finding what you need means guessing keywords, scrolling through irrelevant results, and eventually giving up. Vector databases promised to fix this but only got halfway: compressing a document into a single vector is too coarse to surface the precise match..

Match the part, not the whole

Multi-vector databases change this. Instead of compressing a passage into a single view, they represent it as a set of vectors, preserving the distinct concepts, claims, and evidence inside. When a query arrives, retrieval matches at the token level, so it can surface the exact passages that matter, not just the document that vaguely relates.

This is the difference between "here are 50 documents that mention your topic" and "here is the exact passage that answers your question."

Traditional vector databases often miss the 'needle' because they only index the 'haystack.' NextPlaid’s multi-vector approach preserves the fine-grained details within a document, allowing for matches on specific, granular information that a single-vector representation would typically obscure. This ability to match outside the broad strokes of a document increases the overall accuracy of RAG search. Consequently, the LLM is fed a higher-signal context, enabling it to answer with greater precision and fewer tokens, making the entire system significantly more frugal for enterprise-scale operations.

The search layer for a new era of document intelligence

We have been investing in multi-vector technology for some time, from the development of PyLate to the release of FastPlaid and various state-of-the-art models. While these models and libraries are incredibly powerful, they highlighted a significant friction point in the ecosystem: traditional vector databases are simply not built to handle the fine-grained, token-level requirements of late-interaction models. Until now, teams had to choose between high-performance retrieval and ease of deployment.

LightOn NextPlaid bridges this gap. It is a robust, lightweight and production-ready multi-vector database written in Rust and optimized for CPUs. While our previous release, FastPlaid, serves as a high-throughput GPU batch indexer for bulk offline processing, NextPlaid is the API-first serving layer designed for live environments. It handles documents as they arrive with incremental updates and deletions, allowing you to plug multi-vector retrieval into an established RAG pipeline alongside your existing database without re-architecting your stack. All of that with a simple API for usage and a docker image for deployment.

Technical Deep Dive

NextPlaid is our contribution to making PLAID truly production-ready, so teams can use late-interaction (token-level) retrieval in real systems. If that phrase feels opaque, you’re in good company; this section starts with a simple mental model and builds up from there. The one thing to remember is: PLAID makes multi-vector retrieval affordable by searching only the most relevant parts of the index, and NextPlaid makes that pipeline shippable and easy to operate. Beyond the API layer, NextPlaid extends PLAID itself with incremental index updates and SQL-based metadata pre-filtering to make it viable in production systems.

A quick mental model

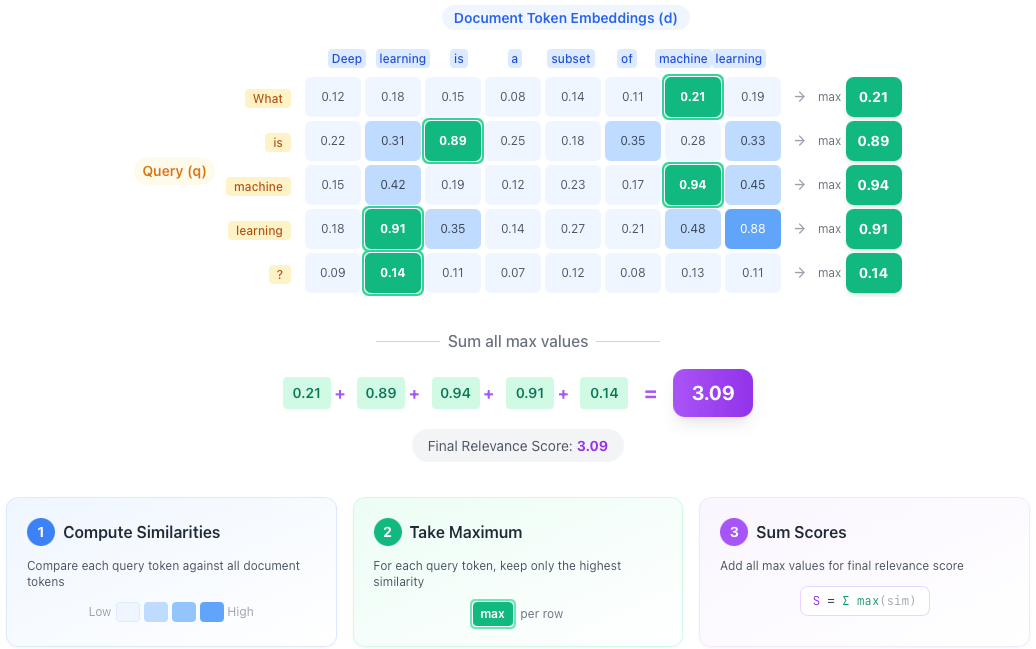

Let’s define a few terms: a token embedding is a vector of floats which describe a token of a document, so documents and queries are sequences of vectors (as a rough mental model, ~300 token embeddings per document, each 128 dimensions or lower). Late interaction, also called MaxSim, means that for each query token you take the maximum similarity against any document token, then sum across query tokens.

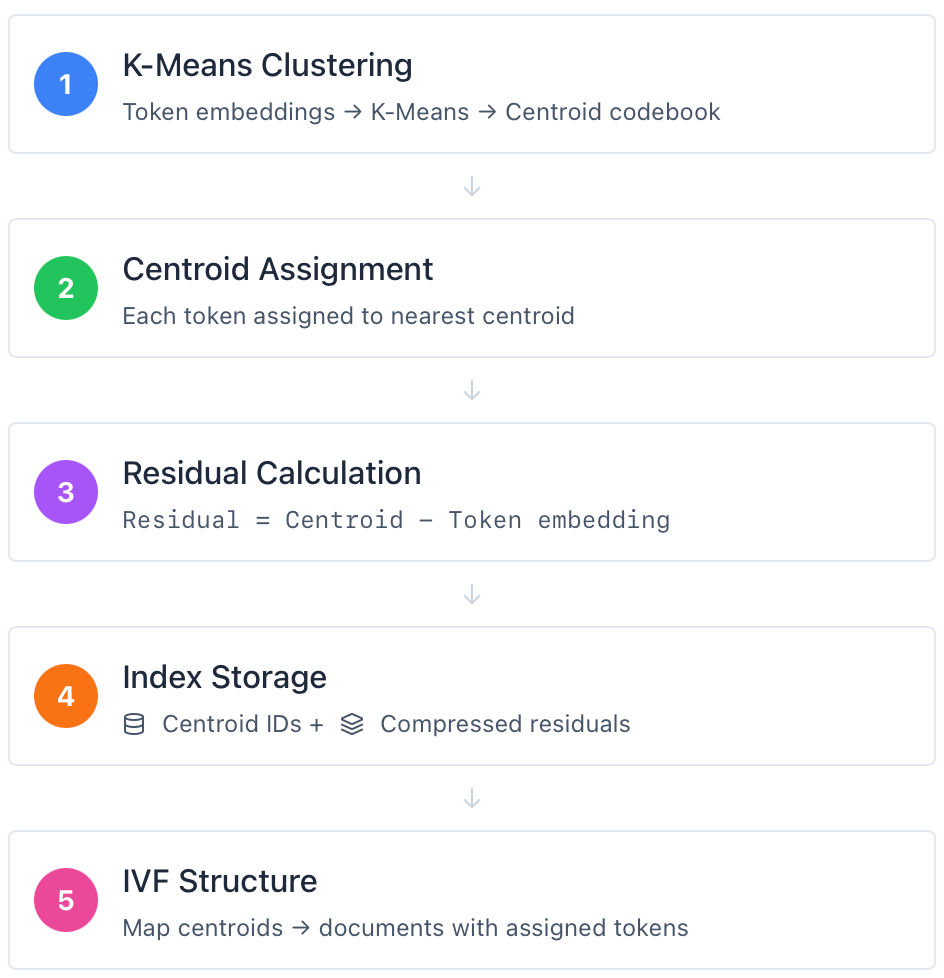

To make this practical at scale, we first cluster token embeddings. A centroid (codebook entry) is a K-means cluster center, and each token is assigned the ID of its nearest centroid. Rather than storing every full token vector, we store the centroid ID plus a compressed residual (the small difference between the token embedding and its centroid).

Now the retrieval part. Think of the IVF index as an address book. Each centroid is a “topic neighborhood,” and the address book tells you which documents live in that neighborhood. In PLAID that’s literally what IVF stores: a mapping from centroid ID to a list of document IDs that contain tokens assigned to that centroid. At query time, we first identify the neighborhoods the query is most likely to care about, then we only open the address-book pages for those centroids and pull candidates from their document lists. That way we only compute a relevant subset of documents instead of scanning the whole collection. Once those terms are clear, everything else is just plumbing and a few production details that matter.

Why late interaction is worth it

Single vector retrieval compresses an entire document into one embedding. It is fast, but it can be brittle on long documents, mixed topic documents, and cases where the query matches a small region that gets averaged away. Late interaction avoids that averaging by keeping token level structure and scoring with MaxSim. The price is that multi-vector search is expensive unless you can avoid doing it over most documents.

PLAID in one page

At indexing time, all document token embeddings are clustered with K means to form a centroid codebook. Each token embedding is assigned to its nearest centroid, which produces a centroid ID plus a residual relative to that centroid (centroid minus the token embedding). The index stores centroid IDs and compressed residuals, and it builds an IVF structure that maps each centroid to the documents that contain tokens assigned to it.

At query time, the system embeds the query into token vectors, scores those query tokens against the centroids, and probes only the best scoring centroids. It then scores candidate documents approximately and finally reranks a much smaller set with exact MaxSim. This is the core PLAID idea. NextPlaid’s contribution is not algorithmic novelty. It is turning this pipeline into a system you can actually operate.

What happens per query in PLAID

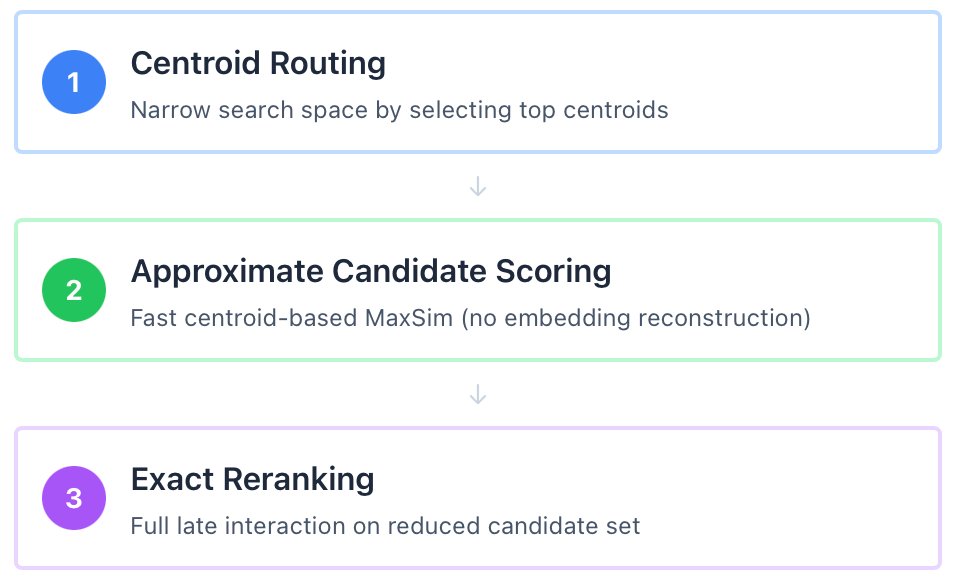

A query flows through three stages that progressively spend more compute on fewer candidates. First comes centroid routing. The query is embedded into token vectors, query tokens are scored against the centroid codebook, and the system selects a subset of centroids to probe. A centroid score threshold can also be applied so low scoring centroids are never probed even if they fall within the top list.

Next comes approximate candidate scoring. PLAID does not reconstruct document embeddings at this stage. Instead, it performs a centroid-level MaxSim: the query-to-centroid dot products already computed during routing are reused as a lookup table. For each candidate document, the system reads its token-to-centroid assignments, and for each query token picks the highest-scoring centroid among those the document's tokens belong to, then sums across query tokens. This stays fast because it operates on compact integer codes and a small pre-computed score matrix. Residuals are not involved, so there is no decompression overhead. This step produces a restricted candidate pool that will then be accurately scored.

Finally comes exact reranking. Only for the reduced candidate set, PLAID reconstructs the needed document token embeddings as centroid plus residual and computes exact MaxSim. The whole point of the pipeline is that you only pay the full late interaction cost after you have narrowed the search space enough to justify it.

What is stored in the index

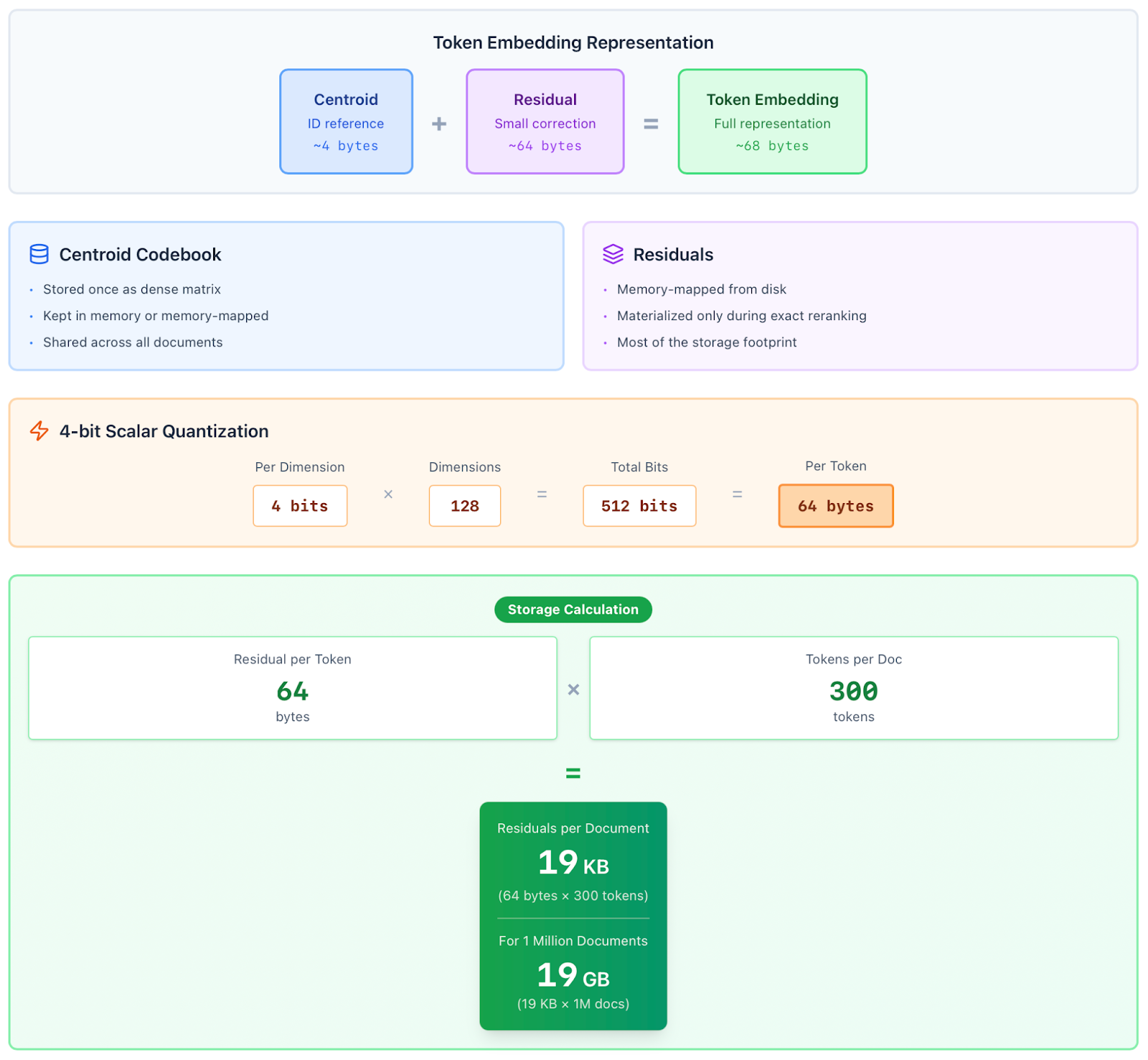

Think of each token embedding as “centroid + small difference between original token embedding and the centroid.” PLAID stores the centroid choice (an ID) and the correction (a residual) for every token. The centroids themselves, the codebook, are stored once as a dense matrix and can be kept in memory or memory-mapped from disk.

Residuals still take most of the space, so NextPlaid memory-maps them and only materializes full token vectors when it really needs them, during exact reranking.

Residuals are compressed with 4-bit scalar quantization per dimension. The quantization buckets are learned globally from the residual distribution, rather than using per-centroid codebooks or heavier schemes like product quantization.

Rule of thumb: 128 dims (embedding size of a single token) × 4 bits works out to ~64 bytes per token for residuals. With ~300 tokens/doc, that’s ~19 KB/doc in residuals alone.

Runtime choices

NextPlaid is written entirely in Rust and is CPU first. Instead of loading whole indexes into RAM, it memory-maps them from disk. That keeps startup fast and lets multiple processes serve the same index without duplicating memory.

On the query path, the system is multi-reader because search mostly reads compact, memory-mapped structures and can run safely in parallel. On the write path, it is single-writer per index.

With only one process writing at a time, the on-disk index format stays consistent and safe. That lets all the readers stay simple, which keeps searches fast and stable.

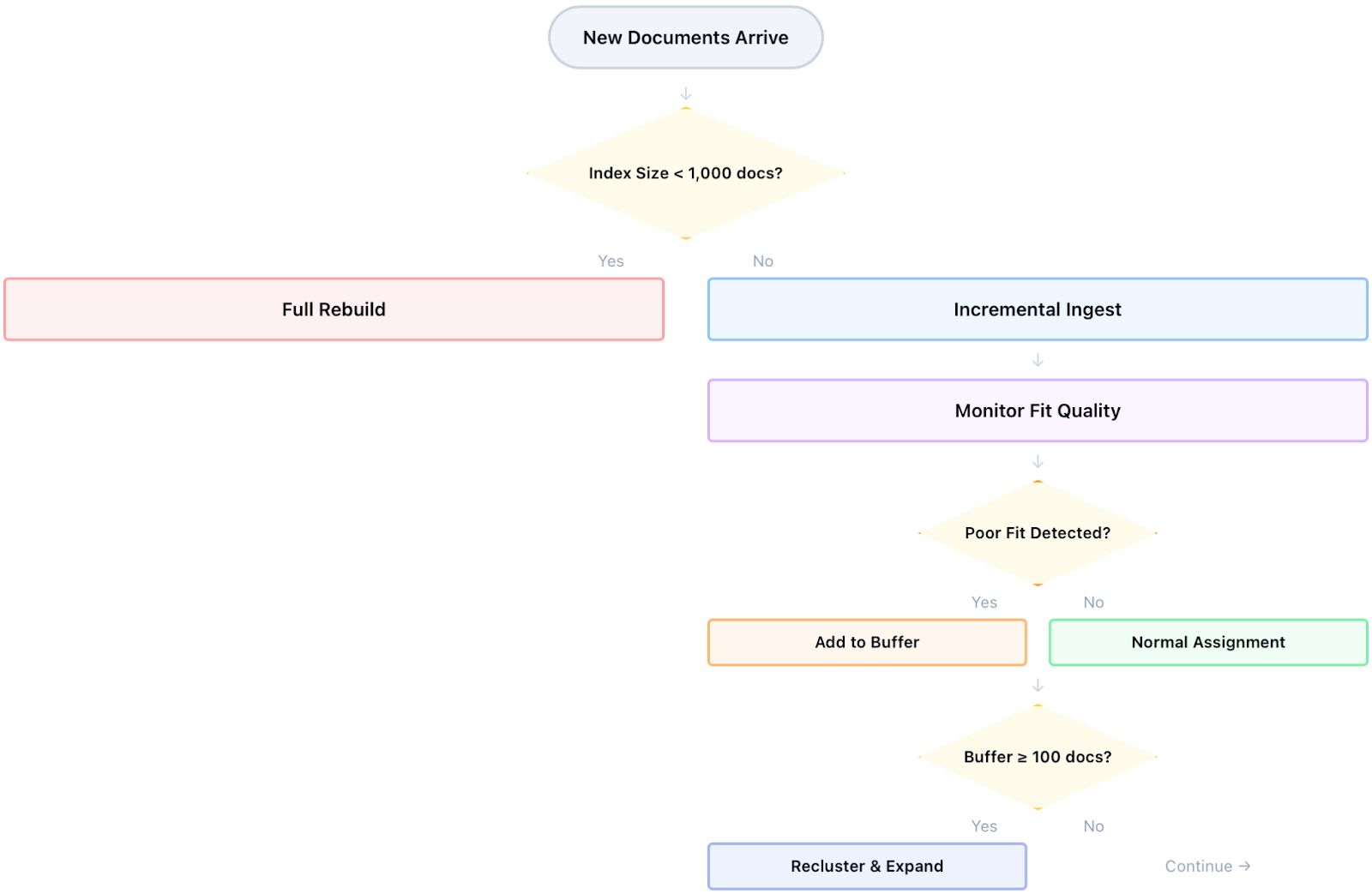

Incremental updates

PLAID is naturally described as a batch algorithm, but real systems ingest continuously and rebuilding for every small update is not viable. NextPlaid supports incremental updates by appending new documents against the current codebook. There is one pragmatic exception. Below 1,000 documents, it rebuilds from scratch because rebuild cost is small and the batch result is the most stable baseline. Beyond that point it switches to incremental ingest, assigns new embeddings to their nearest existing centroids, and appends centroid IDs and quantized residuals into the existing structures.

This works until the data distribution shifts and the centroïds do not accurately represent the distribution anymore. Some new embeddings become a poor fit for the current centroids. NextPlaid detects these poor fit embeddings using an adaptive distance threshold based on residual norms. The threshold is driven by the 0.75 quantile of assignment distances for newly ingested embeddings and blended over time so it adapts smoothly as the index grows. Embeddings beyond that threshold are still assigned a centroid so they remain retrievable, but they are also placed into a dedicated buffer.

When the buffer reaches 100 documents, NextPlaid clusters the buffered embeddings, appends the resulting new centroids to the codebook, removes the previous buffered assignments, and reinserts those embeddings using the expanded codebook. This buffer plus periodic reclustering approach tracks batch behavior surprisingly well in streaming ingestion while avoiding the operational cost of frequent full rebuilds.

Growing the centroid set does have a cost because routing must score against a larger codebook. NextPlaid keeps latency sane by allowing a centroid score threshold that aggressively prunes low scoring centroids and by scoring centroids in batches so memory use stays bounded. If you need a hard reset, rebuilding remains the cleanest option. The incremental path is designed to be operationally cheap, not maintenance free.

Deletion of documents

NextPlaid deletes data by rewriting the index. When you delete documents, it removes them from the on-disk files and rebuilds the IVF lists from what’s left. That means searches don’t have to check “is this deleted?” flags, so the query path stays simple and fast with memory-mapped files. The downside is that deletes are a heavier operation, more like periodic maintenance than an instant toggle.

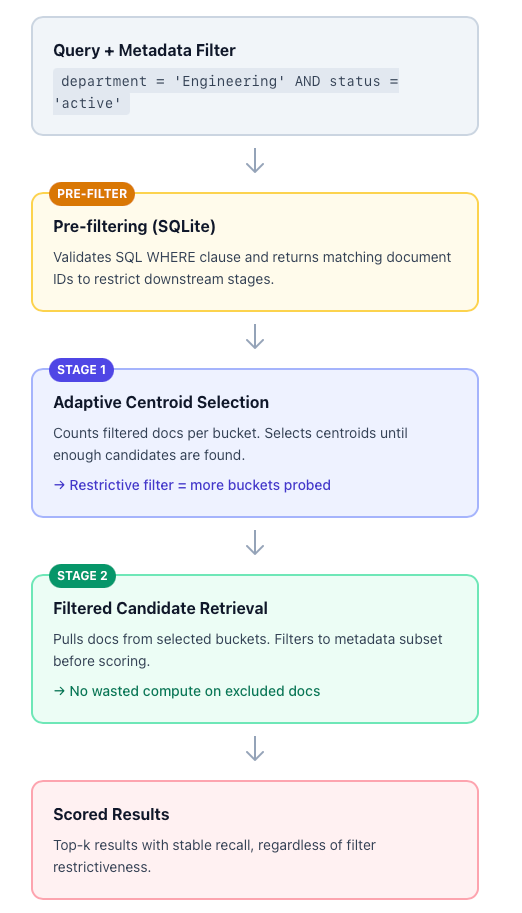

Filtered search without recall collapse

NextPlaid supports filtered search out of the box: document metadata is stored alongside the index in an embedded SQLite database. Filtering happens in two places: first, a metadata pre-filter selects which documents are eligible; then, an adaptive step inside the retrieval pipeline avoids recall collapse.

Pre-filtering with metadata

Think of this as filtering before you search. Document metadata lives in SQLite alongside the index, with fields such as department, date_created, or status. When you ingest metadata, NextPlaid infers SQL column types from JSON values and validates column names.

At query time, you provide a SQL WHERE condition (e.g., department = ? AND status = ?) with parameterized placeholders. NextPlaid validates the predicate against a strict allowlist grammar to prevent SQL injection, executes it to retrieve matching document IDs, and uses those IDs as a subset that constrains all subsequent retrieval stages. In other words, if you filter to “only Engineering documents created in 2024,” the vector search only considers those documents.

Two-stage filtering inside the search pipeline

Once a metadata subset is defined, NextPlaid applies filtering at two distinct points in the retrieval pipeline. This is what prevents recall collapse.

Stage 1: centroid selection. Multi-vector retrieval first identifies the most relevant “buckets” (centroids) for a query, then searches only documents inside those buckets. This is what makes the system fast: most of the index is skipped.

However, restrictive filters can break this assumption. If you probe 8 buckets containing 10,000 documents, then apply a metadata constraint like status = 'archived' AND region = 'EMEA', those 10,000 might shrink to 50 eligible documents. Your top-k results are now drawn from a much smaller pool, and you may miss better matches that sit in buckets you never probed. Classic recall collapse.

NextPlaid addresses this with adaptive IVF probing. When a metadata subset is present, the system counts how many eligible (filtered) documents exist per bucket, then selects buckets by relevance until it has accumulated at least k filtered candidates. If the filter matches only ~2% of the index, NextPlaid automatically probes more buckets; if it matches ~80%, it probes fewer. The probing budget adapts to ensure you always have enough candidates.

Stage 2: candidate retrieval. After selecting buckets, NextPlaid retrieves candidates from those buckets and immediately filters them to keep only documents in the metadata subset. This happens before approximate scoring, so compute isn’t wasted scoring documents that will be discarded anyway.

To further accelerate the filtering stage, we might even pre-compute some of the statistics of the database but we leave it as a next-step.

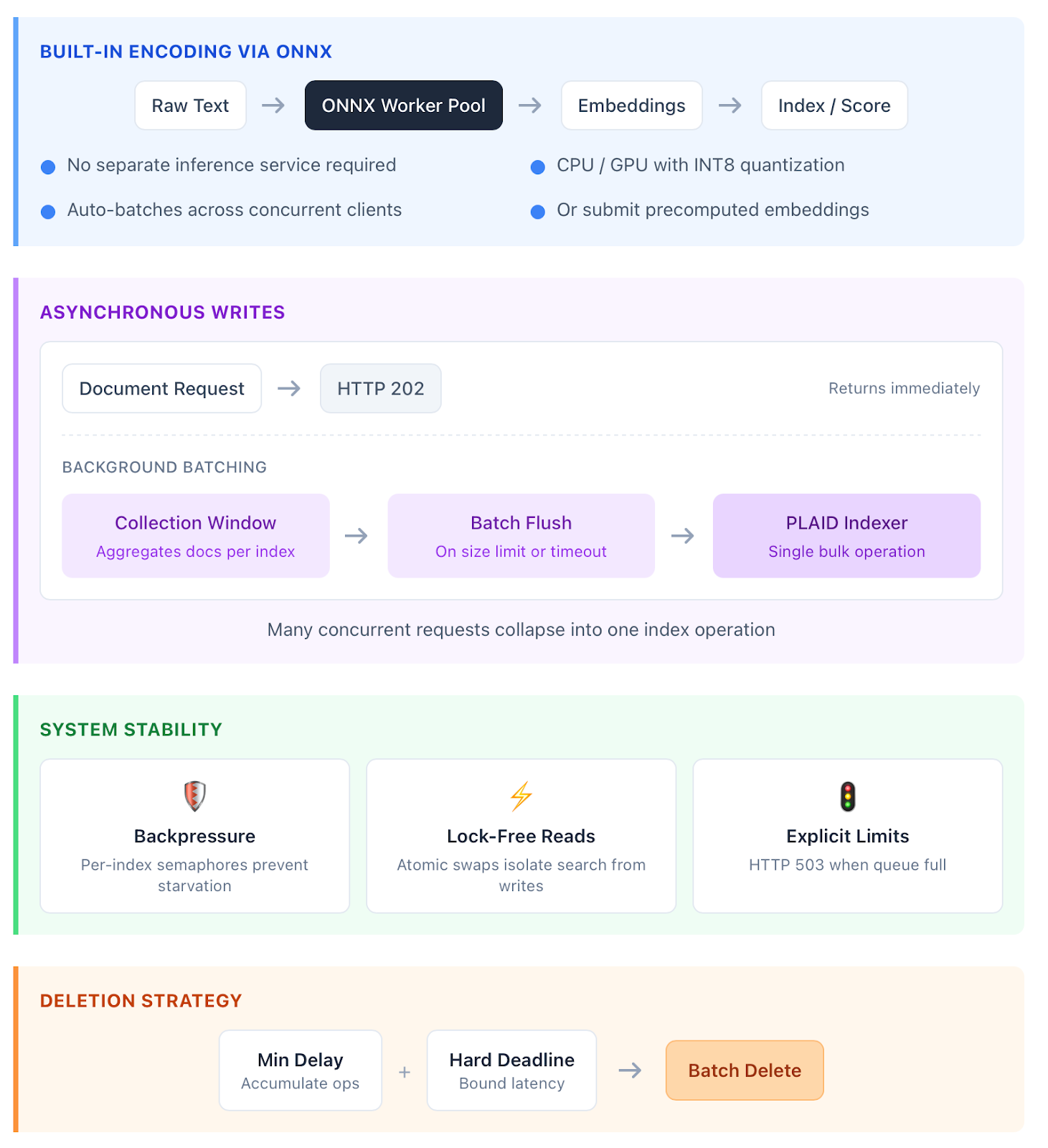

API features

The API provides a complete set of endpoints for index management, document ingestion, search, metadata operations, encoding, and reranking. Encoding and reranking run inside the API via ONNX runtime, so you don’t need a separate inference service: clients send raw text and the API encodes it and then indexes or scores it in the same request. Models can run on CPU or GPU, INT8 quantization is supported, and if you already operate your own embedding pipeline you can skip built-in encoding and submit precomputed embeddings. Internally, encoding is handled by a pool of ONNX workers, each with its own model instance. The API batches incoming texts across clients (grouped by input type and pooling factor), so concurrent requests automatically share inference work without any client-side coordination.

Writes are asynchronous: document updates and deletions return immediately with HTTP 202 while the API performs the work in the background. To maximize throughput, since PLAID indexing is most efficient in bulk, the API actively batches ingestion. When the first document arrives for an index, the API opens a short, configurable collection window and aggregates subsequent documents for that same index into a single batch before sending it to the indexer. If the batch reaches its size limit, it flushes immediately; if traffic is light, the timeout ensures documents are not delayed for long. Under load, many concurrent client requests can collapse into a single index operation, which is exactly the workload PLAID handles best. Deletions follow the same approach, using a two-stage timing strategy: a minimum delay to allow operations to accumulate, followed by a hard deadline to keep latency bounded.

To protect overall system stability, per-index semaphores provide backpressure so heavy ingestion on one index can’t starve others or exhaust shared resources. If the queue is full, the API returns HTTP 503 rather than degrading silently. Reads are isolated from writes: indices are published using lock-free atomic swaps, so search traffic is never blocked by ongoing updates. The result is an API that supports concurrent producers and consumers without requiring clients to manage contention, ordering, or coordination.

Retrieval with less Infrastructure

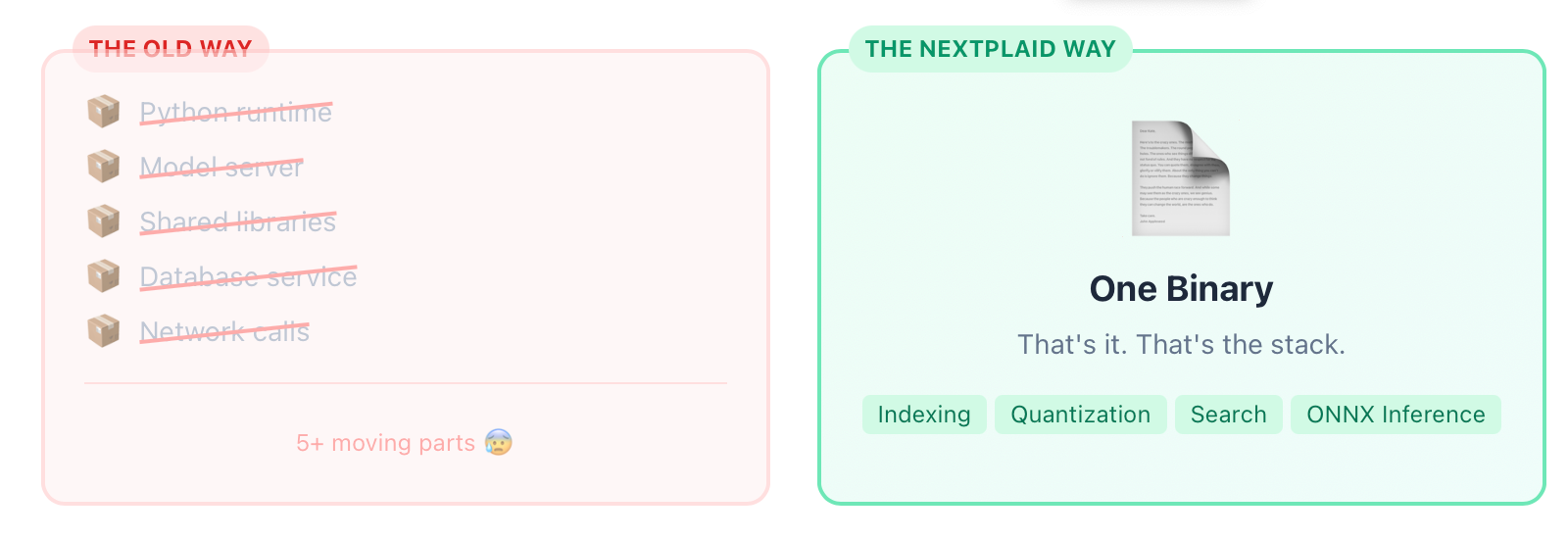

While today we’re releasing the API, we also want to zoom out for a moment. The API is useful: it gives you a clean, scalable way to integrate multi-vector retrieval into applications, with indexing, search, and ONNX-based encoding and reranking behind familiar HTTP endpoints. But the more interesting question is what happens when you don’t need the API at all.

Because NextPlaid is written entirely in Rust, the full retrieval stack (indexing, quantization, search, and ONNX-based inference) compiles into a single self-contained binary. There’s no Python runtime, no model server, and no shared libraries to install. That property changes what you can do with multi-vector retrieval: instead of deploying a service, you can embed retrieval directly into a tool that ships as one file and runs on any machine.

Pair that with a ColBERT model small enough for CPU inference and an on-disk index that supports incremental updates, and you get a retrieval engine that lives next to the data rather than behind an API. This unlocks environments where “install a database” isn’t feasible but “download a binary” is, and it opens the door to workflows that look less like “query a remote service” and more like “carry retrieval in your pocket”.

So yes, the API is what we’re shipping today. But we think the real trajectory is getting rid of as much infrastructure as possible: fewer moving parts, fewer services to operate, and retrieval that can be pulled into agentic tools as a local capability. If you’ve read this far, stay tuned—in the coming days we’ll share something that takes this idea to its logical next step. More soon.

Authors: Raphaël Sourty, Hélen d’Argentré

Careful reviewers: Amélie Chatelain, Antoine Chaffin, Igor Carron

To go further, NextPlaid is available at https://github.com/lightonai/next-plaid, FastPlaid at https://github.com/lightonai/fast-plaid for GPU accelerated index creation that produces indexes NextPlaid can serve, and ColGREP lives in the same ecosystem with quick install paths. Everything is open source under Apache 2.0.

[1] Omar Khattab and Matei Zaharia. 2020. ColBERT: Efficient and Effective Passage Search via Contextualized Late Interaction over BERT. In Proceedings of the 43rd International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval (SIGIR ’20), July 25–30, 2020, Virtual Event, China. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 39–48. DOI: 10.1145/3397271.3401075.

[2] Keshav Santhanam, Omar Khattab, Christopher Potts, and Matei Zaharia. 2022. PLAID: An Efficient Engine for Late Interaction Retrieval. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management (CIKM ’22), October 17–21, 2022, Atlanta, GA, USA. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1747–1756. DOI: 10.1145/3511808.3557325.

.svg)

.avif)

.avif)